Overpopulation and industrial farming - city dweller tells of battery chicken factory night raid

Rendezvous chicken concentration camp

A friend of mine recently invited me to ‘visit’ a factory farm to further my first hand education into the conditions of Australian animals in Victorian factory farms. She has been breaking into intensive animal farms for years, to observe the conditions of these places and to tip off animal rights groups and the relevant authorities when substantial codes of duties have been breached. She wishes to remain anonymous as any public profile may compromise her ability to slip into factory farms incognito. She predicted the experience, whilst unpleasant, would be at least educational and cathartic and that seeing the conditions of these places would catalyse further commitment towards animal liberation.

Why animal activists do not leave it up to the authorities

My friend informed me that she comes across breaches to duty regularly and will anonymously tip off to the relevant authorities as matter of course. The authorities, naturally, rarely act due to lack of will or lack of power, and as expected will tend to act mainly where there are human health and safety issues. Given the inactivity from the forces that should be regulating, she will often take it on herself to rescue the most sick or injured animals. Rescued animals will be nursed back to health at her home before being adopted to loving homes. Although solo rescue efforts will never be recognised by the farmer or their profit margins, (the battery hen farm we visited, for example, houses 30 000 chickens) she can an at least provide a better life for a few individuals who are suffering from neglect and abuse by their ‘owners’ and ignored by the eyes of the law.

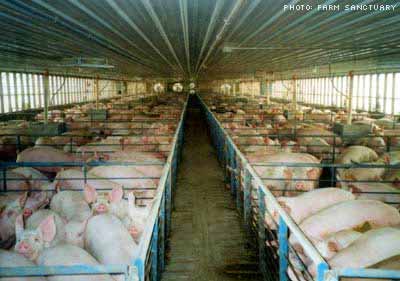

Choosing between an egg or a pig farm

On arrival at my friend’s house she provided me the option of visiting a factory pig farm or a cage egg farm. Both options would involve leaving Melbourne around 10pm - the hen farm was closer than the piggery so we would be returning home at around 3am instead of 6am. As her home was already full of rescued animals and I couldn’t house any myself, I felt it would be easier on her if we brought back rescued chickens. Furthermore, I wasn’t sure that I was emotionally prepared to witness animals as emotionally complex as pigs in such dire circumstances (she told me that you can hear the distressed sounds of pigs up to 1km away from their incarceration and often they sound human). From my perhaps spurious logic, chickens offered a further degree of separation that would make witnessing their plight marginally less gut wrenching.

Covert approach

So off we drove into the night towards an egg farm dressed in black with binoculars (I felt like a spy on a sabotage mission, and in some respects we were). We discussed how we were going to break in; she had visited the farm before and the most direct method was to sneak past the home at the front of the property. However when we arrived by midnight, the lights in the house were still on, precluding direct access to the sheds without being noticed. After waiting on the road for half an hour the lights were still on full force so we decided to take a long cut via the adjacent cow paddock. This required weaving through barbed and electric wire and squeezing through gaps in the fencing, feeling like Harry Houdini on boot camp. As there was a full moon, we had to crawl several hundred metres in the trees and shadows to avoid being sighted by the household or by a worker having a smoko outside the employee sleep quarters. If all that wasn’t tense enough, my co-conspirator has a phobia for cows and was bracing herself for an encounter on the paddock (the irony of an animal liberator being afraid of cows was not lost on either of us). Thankfully the cows proved elusive that night.

Mechanised farming

We could hear the sheds well before we finally saw them in the (suitably) eerie grey moonlight. There was a persistent motorised humming sound derived from the enormous fans at one end of each shed that serve to maintain a modicum of air flow and temperature control. As the sheds themselves appeared fairly innocuous buildings typically found on industrial estates, the low hum was the first indicator of more sinister things at work inside.

The doors to the first shed were not locked but were stiff and would not move until they gave a creaking protest after a shove, ending in a reverberating bang. We stood still or a brief moment in case our cumbersome act had caught attention, but we then realised the fan had completely drowned out the sounds.

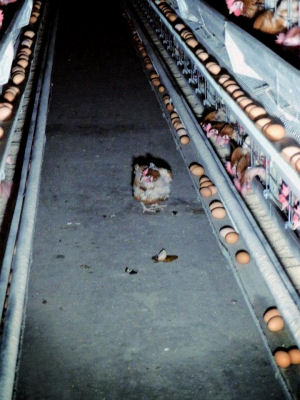

The living inside the machine

It was completely dark inside, and one almost felt alone aside from the hum. However, the nostrils were soon assaulted by that heavy earthy, nitrogenous smell so particular to chicken faeces. Switching on our torches, they shined on a floor of grim, unforgiving concrete mixed with dust, stray feathers and excrement. Then the torches were turned to the centre of the room, revealing numerous concrete partitions running 15 feet from floor to ceiling, like giant cupboards, with narrow pathways running between them.

We walked to the nearest walkway in complete darkness save for the thin slice of torchlight providing a small window in which to navigate ourselves. Once in the walkways we shone the torches to a wall. Almost immediately we were affronted by the visage of five sleeping chickens in a wire cage not much larger than an A3 sheet of paper. The chickens were back to back, side to side, with one almost lying on top of the others as there just didn’t seem to be enough room for all feet to make contact with the wire mesh floor.

It was an image that nearly takes the breath away and just as I remembered to start breathing again a couple of chickens stirred in the light and began quietly cooing. Their vocals whilst soft conveyed to me that they felt every bit as uncomfortable and distressed as they appeared. It was very tempting at that point to open the front chute and take all 5 chickens home with us right then, however we couldn’t practically leave with more than four and this cage certainly was not the only one in the building. To the side, underneath, and above all the way to the roof where the torchlight couldn’t reach, were cage after cage of crammed inmates that stirred as the light passed by them and added to the choir of quiet distress. Underneath each cage was a platform where the eggs collected, many which were partially covered by the excrement from the cage above or by dust from the facility at large, needing a solid clean before looking palatable for the supermarket. These eggs were the source of income and greed that allowed a cheap animal product to be readily available at a supermarket shelf 24/7 by means of exploitation of a vast number of units of production (that just happen to be self aware, sentient beings).

Disorienting scale

The knowledge that we were surrounded by up to 15 000 chickens in that shed but could only see clearly 2 or 3 cages at a time by torchlight gave a warped, disorientating sense of scale, and a sense of being watched in the dark. Shrouding the protagonists in darkness and the unknown is a technique used by rote in horror movies, but unlike fiction, this genuinely felt like walking into the jaws of hell, as depicted by an industrial dystopia where modernism and functionalism have reached their extreme conclusion.

Lifers' inner circle of hell

It would be hard to envision that things got worse from hereon, however this was the shed where the younger chickens had just started laying and had therefore had not being incarcerated for long. The second shed was far worse. Older chickens, nearing the end of their laying cycle moved here, and one could tell by the amount of built up excrement on their bodies in addition to a noticeable lack of feathers for many. I asked my friend whether this was due to being attacked by other chickens or through lack of nutrition and stress. She informed me that the most frequent reason for this is that chickens were plucking THEMSELVES because they had gone mad. In one cage we discovered a recently dead chicken that appeared as a puffy, amorphous lump with feathers; the poor hen had succumbed to an inflammation disease and the other living chickens were still stuck in the cage with her.

Weeks old corpses of chickens left on floor

On walking down the passageways in shed 2, one always needed to be looking down at the floor to avoid stepping on any carcasses. Sometimes a hen may have separated from her cage for a variety of reasons and ended up on the floor. If the chicken is older and approaching the end of her egg laying days she is considered surplus and a waste of effort and opportunity cost to place back in the cage. Such birds are instead left on the floor to die from dehydration, or are stepped and stamped on to break their windpipes and bones to hasten the process. I kid you not that some of the corpses on the passageways must have been weeks old that was both distressing and disgusting.

In the end we rescued four hens; three were alive on the floor and would have succumbed to dehydration had we not picked them up; we also rescued from a cage a hen with almost no feathers left on her. All birds gave a small protest when first handled but soon settled. Two were placed in a sack bag and the other two under our coats (when placed in a dark environment, bird species such as ducks and chickens will pacify and sleep almost instantaneously). Many of the birds now had stirred as we could not rescue any more there was no point in staying for any longer so we walked away to a chorus of a distressed, cooing choir.

Death by neglect in the cages far above keepers' heads

We noted that some of the sounds were sourced from cages far above us; these birds do not get the human interaction, however brief and apathetic it may be, and often get left behind and forgotten during times of ‘product rotation’ – death by neglect is almost inevitable.

Rescuing some of the worst-off survivors

The return journey to the car was made less graceful for having our hands full of chickens. The Houdini feats to get through the gates and fences the first time around had just increased by several levels of challenge. Adamant not to hurt any chickens in any way, we ourselves ended up with quite a few scratches and bruises ourselves (after gently placing the sleeping chickens through the border fence of the property, we made our last and final jump over the electric wire only to land straight in a blackberry bush). Any resulting suffering to us was however nothing compared to how these four brave soldiers had endured their whole lives. Noting that it was now impossible to remain quiet and inconspicuous, we were relieved that the lights on the house had gone off (quite how they sleep soundly at night though is anyone’s guess).

The empowerment of political engagement and humane action

The drive back was a feeling of mixed emotions for me. Exhausted, enervated and teary, I also felt catharsis and an odd sense of thrill at my incident- free go at civil disobedience. I felt empowered by having saved the lives of four individuals. And I have heard they are all at my friend’s house happy and well, in seventh heaven, enjoying sunshine, grass on their feet and room to spread their wings, all rights previously denied. I also felt powerless and small by my inability to save the lives of the other 30 000 chickens, and of course that is in just one egg laying factory farm amongst countless others. There were many questions running laps through my head as we drove off back to Melbourne again, many questions I haven’t found answers for and perhaps never will. I will try to provide a summary of my thoughts through the context of my twin passions of animals rights and human population sustainability

Observations and conclusions

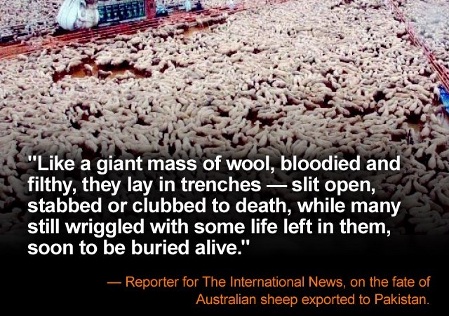

Animal welfare standards

1) My own first hand experience of factory farming more or less correlates with the horror stories one often hears about. Perhaps there weren’t as many broken wings and legs as I was expecting, however the lack of space, the lack of feathers and the complete disregard for the chickens that ended on the shed floor simply beggars belief. Australia probably does have a slightly higher standard of animal welfare compared to some other parts of the world, but this does not mean that it is a HIGH standard by any means nor that we should sit back on our laurels when one is simply comparing between degrees of abhorrent treatment to sentient beings.

Cruelty a feature of industrial scale exploitation

2) Animal exploitation to this degree and scale of abuse and cynicism just to provide people the convenience of an animal product 24/7 at minimal cost makes me question our collective humanity as a species. I am not morally against eating meat fundamentally as to do so would be condemn all societies throughout human history who hunted meat from the natural world, which is a huge call to make. However by treating animals as large scale units of production and depriving them of any quality of life or happiness merely to satisfy an eating preference that we don’t require on a daily basis, I can only reflect on this as fundamentally wrong.

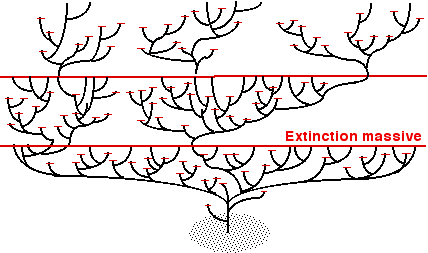

human overpopulation drives industrial-scale farming cruelty

3) In addition to capitalism and industrialisation, one of the contributory factors to factory farming is growing human population. In order to meet the wants of daily animal product consumption of a swelling population, there simply isn’t enough space to put all these animals in land that’s already been cleared of wildlife and used for other human purposes such as agriculture and suburbia. The result is to keep animals in as small an area as possible in artificial environments. As the population grows, free range farming will become increasingly impractical as there won’t be the space. Whilst a growing population destroys other animals through just about any food choice (just look at palm oil), it strikes me as a double whammy to clear a habitat and all the animals that live there only to then fill the space with countless livestock animals who endure suffering for our gain.

Raise awareness that overpopulating Australia decreases our moral choices

4) If there is an answer to any of the above, it would come down to a combination of understanding where your food comes from, eating ethically under the current circumstances (in my case avoiding all animals products) and do anything that one can to raise awareness of the implications of human population and to mitigate further population growth.

Did I enjoy my first factory farm visit at any level? Definitely not. Would I do all of this again?

In a heartbeat.

The first case of H1N1 swine flu virus was discovered in a North Carolina factory farm in 1998, not in Mexico. Within months of the 1998 emergence, the virus showed up in Texas, Minnesota, and Iowa.

The first case of H1N1 swine flu virus was discovered in a North Carolina factory farm in 1998, not in Mexico. Within months of the 1998 emergence, the virus showed up in Texas, Minnesota, and Iowa. Influenza in pigs is closely correlated with pig density,” said a European Commission-funded researcher studying the situation in Europe.

Influenza in pigs is closely correlated with pig density,” said a European Commission-funded researcher studying the situation in Europe.

Recent comments