wildlife habitat

Mass migration isn’t good for Australia, and it’s never “properly planned and well managed”

Sustainable Population Australia (SPA) has questioned the claim by the Business Council of Australia (BCA) that ‘two thirds of Australians believe that properly planned and well managed migration is good for Australia’. BCA has asked a loaded question, to get the answer they wanted. Their result is directly contradicted by the more reliable Australia Population Research Institute survey. Here, 70% want net migration at somewhat or much lower levels than the pre-COVID 240,000.

Vegetation clearing on days of total fire bans and development in guise of reducing fuel load - public should be concerned

Bearing in mind the recent Crib Point tragedy - a suspected arson attack, with wildlife loss yet to be detailed, one home destroyed and one home damaged plus several sheds destroyed, we have to be more vigilant about how and whether we develop our bushland neighbourhoods more densely. Planning laws allow property owners to remove large amounts of vegetation without permission from their land citing their reason as 'fire protection'. After the vegetation is removed, those property owners may apply to the council for permission to intensify development on the land. Council usually does not deny permission for individual cases. But such individual cases mount up and create a danger which councils and planners may not have seen. The risk is that the granting of denser housing development in a bushland area means that, if there is a fire in the remaining bushland, there will be an increased number of residents needing to evacuate. Increasing population density means that more roads are needed to cope with a fire emergency evacuation. However, densification is being allowed to happen in an ad hoc, case by case fashion, without the building of roads in advance of significant development. No-one is overseeing the total impact.

Bearing in mind the recent Crib Point tragedy - a suspected arson attack, with wildlife loss yet to be detailed, one home destroyed and one home damaged plus several sheds destroyed, we have to be more vigilant about how and whether we develop our bushland neighbourhoods more densely. Planning laws allow property owners to remove large amounts of vegetation without permission from their land citing their reason as 'fire protection'. After the vegetation is removed, those property owners may apply to the council for permission to intensify development on the land. Council usually does not deny permission for individual cases. But such individual cases mount up and create a danger which councils and planners may not have seen. The risk is that the granting of denser housing development in a bushland area means that, if there is a fire in the remaining bushland, there will be an increased number of residents needing to evacuate. Increasing population density means that more roads are needed to cope with a fire emergency evacuation. However, densification is being allowed to happen in an ad hoc, case by case fashion, without the building of roads in advance of significant development. No-one is overseeing the total impact.

Vegetation clearing on days of total fire bans

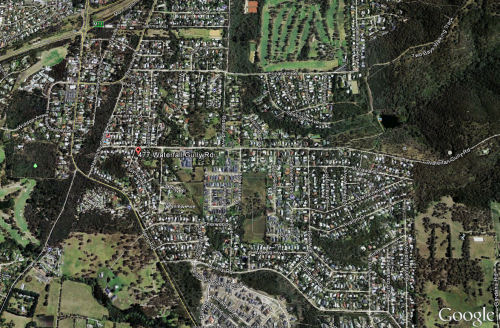

477 Waterfall Gully Rd Rosebud 3939 Victoria.

Clearing took place on Friday 15/1/16, Monday 18/1/16 and Tuesday 19/1/16 thus far.

To date up to 45 trees and shrubs have been removed, including 4 manna gums. One which was a hollow bearing tree and one on a neighbouring property. Most of the other vegetation removed was coast tea-tree.

I called the Mornington Peninsula shire council's planning department, on the 18th and 19th of January about the clearing of vegetation. The officers I spoke to on both days confirmed that there are no permits for either vegetation clearance or an application permit for a building extension/residential development. The planning department said that the vegetation clearance was legal without a permit. As the vegetation in question was within 10 meters to the residence or 4 meters within the property boundary.

As the primary reason that fire regulations allows for the vegetation clearance. I have raised the following concerns;

No 477 Waterfall Gully residence has been unoccupied since November, when it was sold. That the first action of the owner is to remove all trees and shrubs from site would suggest it is being cleared for a development - an opinion shared by the professionals clearing the vegetation and by the surrounding neighbours.

Two of the three days the vegetation being cleared were days of total fire ban. The 18th and 19th of January were days of total fire bans. The use of multiple heavy industrial petrol operated equipment on days of total fire ban, I believe, makes a mockery of fire prevention laws.

The planning department understand my concerns and have been as helpful as they can. However there is nothing they can do to address this issue due to current regulations. So I ask your assistance in addressing flaws in the fire regulations that allow developers to exploit them. These flaws are:

To ban activities such as clearing vegetation or activities that could cause fires on days of total fire bans,

Close loop holes that developers use to clear vegetation under false pretences, which cost the Shire revenue.

Further considerations on this matter

Neighbourhood character

The character of a neighbourhood defines the people and families that live in an area. Many of these people who live in community make real value contributions to the neighbourhood character by volunteering their time. It is of great disappointment that potential developers ( who more often than not, do not live in the neighbourhood) use inequities in planning laws to change a neighbourhood character for financial gain.

Health and Wellbeing

Waterfall Gully Rd/ South Rosebud is a bushy area and as such creates a certain atmosphere to the suburb. Residing in a beautiful neighbourhood therefore contributes to a mentally healthy state of its residents. The removal of trees for more dwellings creates a heat island. As our population ages heat stress related illnesses is becoming a more of an issue. Noise pollution from vegetation clearance and building is another factor of having a major impact on health and well being.

Overdevelopment and emergencies

Planning laws allow property owners to remove large amounts of vegetation without permission from their land citing their reason as 'fire protection'. After the vegetation is removed, those property owners may apply to the council for permission to intensify development on the land. Council usually does not deny permission for individual cases. But such individual cases mount up and create a danger which councils and planners may not have seen. The risk is that the granting of denser housing development in a bushland area means that, if there is a fire in the remaining bushland, there will be an increased number of residents needing to evacuate. Increasing population density means that more roads are needed to cope with a fire emergency evacuation. However, densification is being allowed to happen in an ad hoc, case by case fashion, without the building of roads in advance of significant development. No-one is overseeing the total impact. Most people who choose to live in bushland area would not approve of significant intensification of development. They would need to be alerted to any plans to build new roads for a planned increase in population and would probably object to significantly increased population plans. They are not being alerted, the roads are not being built, but the densification is happening in an unplanned fashion. This is dangerous. If a fire emergency was to threaten South Rosebud, Jetty Rd is the main route to escape!

Wildlife

Even though wildlife are protected, there never seems to be any enforcement to protect them. Up to 45 trees and shrubs were cleared at 477 Waterfall Gully Rd. What happens to those animals who have now lost their home?

Owls' legal case and plans to burn Victoria's native forests for fuel

The protection of owls might soon go to the Supreme Court and a proposed regulatory change will allow native forest wood to be burnt for electricity. It was been tabled in the House of Reps today, 27 May 2015. There is a danger that Bill Shorten's Labor Party might support the bill, despite what that says about our renewable energy scheme. Read on to find out how we might fight this.

The protection of owls might soon go to the Supreme Court and a proposed regulatory change will allow native forest wood to be burnt for electricity. It was been tabled in the House of Reps today, 27 May 2015. There is a danger that Bill Shorten's Labor Party might support the bill, despite what that says about our renewable energy scheme. Read on to find out how we might fight this.

Owls' Legal Case

The court-ordered mediation with the department and VicForests last week did not resolve.

The next step is a Directions hearing on the 26th of June to have the matter heard in the Supreme Court.

We can’t give you much more detail than that at this stage. In the meantime, tell Minister Neville and her Department to protect our rare Owls and their forest in East Gippsland. And if you’d like to help us along with this 4th legal challenge (so far we’ve won or settled 3/3) click here to make a tax-deductible donation.”

Read the background to this case here

Bill tabled to burn forests as ‘renewable energy’

The regulatory change that will allow native forest wood to be burnt for electricity has been tabled in the House of Reps today.

It looks like Bill Shorten’s Labor Party might support the bill, even though it means undermining our renewable energy scheme. This is urgent. Please make a quick phone call to Bill Shorten's office and urge that Labor opposes this. (02) 6277 4022.

If Labor opposes this, the vote will be decided by the independents on the crossbench in the Senate. The Senate sits again on June 15, so contact the cross benchers and let them know that you want them to vote against the change to the regulation.

A few suggested points to raise are available here

Some of the crossbenchers have been concerned that the industry will need certainty, and Labor could reverse the regulatory change next in government, so that uncertainty is a point to raise as well. Plus, many still believe the lie that the ‘waste’ will only be the heads and sweepings (!) There needs to be a very clear definition provided before anyone votes on this.

From our experience, emails are good but can get ‘lost’, so phone calls or tweets are better.

|

Ricky Muir (03) 5144 3639 [email protected] Glenn Lazarus (07) 3001 8940 [email protected] Nick Xenophon 08 8232 1144 [email protected] John Madigan (03) 5331 2321 [email protected] Dio Wang (08) 9221 2233 [email protected] David Leyonhjelm (02) 9719 1078 [email protected] |

|

Matthew Guy must DO THE RIGHT THING BY THEM – REJECT FRANKSTON COUNCIL’s REQUEST

Dear Minister Matthew Guy,

You are obviously gung ho for political advancement!

You appear to do anything to appease those with the loudest voices as well as all developers.

We ask you to please consider native animals which have no voice but ours.

NATIVE ANIMALS NEED YOUR HELP MINISTER GUY!

DO THE RIGHT THING BY THEM – REJECT FRANKSTON COUNCIL’s REQUEST

DO THE RIGHT THING FOR KOALAS especially !

"Planning" must encompass more considerations than just stretching urban boundaries

Mr Matthew Guy, Minister for Planning, Victoria

Level 20

1 Spring Street Melbourne 3000

Dear Sir,

Re: resolution that was passed by the Frankston Council on 20 Jan ’14 that Council writes to the minister requesting authorisation to prepare and exhibit an amendment to the planning scheme covering the rezoning of 42 ha of green wedge land in Stotts Lane, Frankston South for residential subdivision.

The resolution was passed 5:4 on the vote of the Mayor.

The Australian Wildlife Protection Council (AWPC) Inc believes you should reject Frankston Council’s request:

Already Franston's Green Wedge nibble at

Frankston should not lose any more Green Wedge, after such huge loss to Peninsula Link, and recent rezoning for Peninsula Private hospital development. Development in this area will see the loss of land currently classified as Rural Conservation Zone which is covered by a Significant Landscape Overlay.

Habitat clearance is the greatest threat our wildlife faces today ; the land in question would further deplete what was a significant bio-link between the listed RAMSAR Seaford wetlands and the listed RAMSAR Westernport wetlands.

Native animals need habitat, or they die!

This land is an important habitat corridor for Koalas. Every spring male koalas migrate from Cranbourne Botanical gardens to mate with the female population that lives in Frankston South. Since Peninsula link opening there have been two male koalas killed on the freeway. If this vital link is lost the South Frankston Koala population will be locally extinct

There is continual loss of habitat in this area due to the new freeway, and little to no offsets in Frankston.

There is increased competition for habitat amongst wildlife, and more vulnerable species such as sugar gliders and woodland birds especially the the eastern yellow robin will also become locally extinct.

Local wildlife shelters are faced with a number of problems

An increase of wildlife that needs care - Less habitat to release rehabilitated wildlife

This means:

- We need to find more volunteers to help run our shelters - We need find more funds to rehabilitate and feed wildlife

- If we are unable to meet those needs we have to limit our services which obviously causes stress to both us and the community member we are unable to help.

Stotts Lane has strong conservation values that need preserving, and shouldn't be dug up for housing

The applicant has engaged BL&A to prepare a Flora and Fauna Assessment Report. This report recognises that the land contains areas of vegetation of high conservation and the area is of very high conservation significance.

-The Report states on page 10 that the property “displays good habitat connectivity”, indicating a connection between Langwarrin Flora and Fauna Reserve and Frankston Natural Features Reserve via patches of remnant bushland. The report goes on to state on page 24 that

This "Planning" violates previous planning policies

The proposed change flies in the face of:

-The long standing bi-partisan support for protecting Melbourne's Green Wedges.

-The State and Local Planning Policies for protecting Melbourne’s Green Wedges.

-Plan Melbourne's initiative to establish a permanent metropolitan urban boundary.

-The strategy quoted in Planning Scheme Clause 11.04-5 - Melbourne Urban Growth:

Contain urban development within the established urban growth boundary. Any change to the urban growth boundary must only occur to reflect the needs demonstrated in the designated growth areas.

Protected land for wildlife and conservation is not an "anomaly"

In 2011 Frankston Council refused a request for the land to be treated as an ‘Anomaly’ in the Review of Urban Growth Boundary Anomalies Outside Growth Areas. An amendment to rezone the land to a residential zone was also refused by the then Minister for Planning in August 2004.

No strategic justification has been put forward for the proposal; instead it has been assessed on a purely ad hoc basis without taking into consideration the wider implications. . Regrettably, to date, Council has not undertaken a Green Wedge Management Plan that would provide guidance on the future management and planning for the Green Wedge.

Population is being "projected" but not land for native animals and vegetation

There is no need for additional residential land in the municipality because, as stated out in Council's Housing Strategy. Frankston's projected population can be accommodated within existing urban areas.

The proposal is opposed by the Mornington Peninsula Shire Council, Federal MPs Mr Bruce Billson and Mr Greg Hunt, and State MP Mr David Morris. We understand that the Member for Frankston, Mr Geoff Shaw, is also opposed to the proposal as is Mr Johan Scheffer the Member for Eastern Victoria Region.

The proposed would result in the urban sprawl extending down onto the Mornington Peninsula and would eliminate the break that separates the township of Baxter from the urban area of Frankston.

This is in direct conflict with the Draft Frankston Housing Strategy (para 1.2.1), which states that the “South East and Mornington Peninsula Green Wedges provide a limit to the region’s growth to the south and east.”

Approval of the application would mean the loss of pleasant, picturesque, rural properties that contain stands of mature, native trees that provide valuable habitat and vegetation that is classified as being of very high conservation significance. The importance of the scenic value of the area is recognised in the Planning Scheme by it being covered by a Significant Landscape Overlay.

Proper planning transcends ticking housing approvals and opportunities for developers

Approval of the application would create uncertainty and encourage more such opportunistic proposals. This was acknowledged in the officer report in the agenda for the meeting which stated:

Council and Officers have been contacted by representatives for other land holders outside the Urban Growth Boundary in regards to either their future plans with their land or enquiring of Council’s view to future urban rezonings.

An enquiry in the north of the City is suggesting rezoning 356 hectares to residential, centrally in the city 22 hectares to industrial use; and to the south 8.6 hectares to residential.

This proposal has no justification, is contrary to State and Local Planning Policies, would set a dangerous precedent and urge you to refuse to authorise the Council’s request to prepare and exhibit an amendment to the planning scheme.

The Green Wedge must be maintained to protect its conservation, recreation and agricultural values. Green Wedges have played an important part in making Melbourne the 'World Most Liveable City'. Frankston’s Green Wedge makes a substantial contribution to the mental and physical health of the community.

Current planning is ad hoc, destructive and opportunistic instead of being holistic

Current planning laws only take into account wildlife value or need for protection if it is deemed threatened, and even then that is always not enough to secure protection.

Do the Right thing please Minister Guy

Kind regards

Maryland Wilson, President Australian Wildlife Protection Council

Protected Habitat Doubles for Magnificent and Endangered Blue-throated Macaw

(Washington, D.C., January 2, 2014) Bolivia’s Barba Azul Nature Reserve, home to the world’s largest population of the majestic Blue-throated Macaw, has been doubled in size through efforts led by Asociación Armonía, Bolivian partner of American Bird Conservancy (ABC). Asociación Armonía and several partner groups worked together to purchase an additional 14,820 acres that have expanded Barba Azul Nature Reserve from 12,350 acres to 27,180 acres. The reserve is the only protected savanna in Bolivia’s Beni bioregion that is spared cattle grazing and yearly burning for agricultural purposes.

(Washington, D.C., January 2, 2014) Bolivia’s Barba Azul Nature Reserve, home to the world’s largest population of the majestic Blue-throated Macaw, has been doubled in size through efforts led by Asociación Armonía, Bolivian partner of American Bird Conservancy (ABC). Asociación Armonía and several partner groups worked together to purchase an additional 14,820 acres that have expanded Barba Azul Nature Reserve from 12,350 acres to 27,180 acres. The reserve is the only protected savanna in Bolivia’s Beni bioregion that is spared cattle grazing and yearly burning for agricultural purposes.

"Blue beard"

“Barba Azul” means “Blue Beard” in Spanish and is the local name for the Blue-throated Macaw, which only occurs in Bolivia and is listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature). It was also recently listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. The Barba Azul Nature Reserve is the world’s only protected area for the Blue-throated Macaw; the reserve has hosted the largest known concentration of these birds, with close to 100 recorded on the reserve at times. (More on these critically endangered and historically sought after large, intelligent, long-lived social parrots)

International wildlife conservation effort

“Conservation actions of this magnitude for small organizations in poor countries are only possible with outside help. Doubling the size of the Barba Azul Nature Reserve is an excellent example of conservation groups combining their effort to achieve a massive conservation product,” said Bennett Hennessey, Executive Director of Asociación Armonía.

Several organizations and individuals teamed up to achieve this historic conservation result: American Bird Conservancy, Patricia and David Davidson, International Conservation Fund of Canada, IUCN NL / SPN (sponsored by the Netherlands Postcode Lottery), Loro Parque Fundación, Rainforest Trust, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service’s Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Act Grants Program, Robert Wilson Charitable Trust, and World Land Trust.

Forests, grasslands, and wetlands are all protected thanks to the new lands (see photo) acquired to extend the Barba Azul Nature Reserve. The extension of Barba Azul includes two large palm forest islands, an essential foraging area for the Critically Endangered Blue-throated Macaw, as well as a forest home for many arboreal mammals and birds. Photo by B. Hennessey, Asociación Armonía.

The reserve extension protects broad grassy plains of the Beni savanna that are seasonally flooded in the rainy season. Also included in the newly protected area are a small river as well as “islands” of tropical forest characterized by tropical hardwoods and palms in this sea of grass. Two large forested islands provide crucial foraging habitat for Blue-throated Macaws, while more than 20 small forested islands provide roosting and potential nesting sites for these birds.

“The small forested islands appear to be great sites to use artificial nest boxes to attract Blue-throated Macaws to breed here,” Hennessey added. Armonía is currently working at the reserve to attract Blue-throated Macaws to artificial nest boxes, with support from ABC, Bird Endowment, Loro Parque Fundación, and the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund.

Reserve supports about 250 more bird species

In addition to the macaw, the Barba Azul Nature Reserve supports roughly 250 species of birds. The tall grasslands provide habitat for the Cock-tailed Tyrant and Black-masked Finch, both listed as Vulnerable by IUCN, as well as healthy populations of the Greater Rhea (Near Threatened) and migratory Bobolink from North America. Extensive wetlands attract flocks of waterbirds, including the Orinoco Goose (Near Threatened), which use nest boxes on the reserve. Armonía staff observed more than 1,000 Buff-breasted Sandpipers on the reserve in 2012, making Barba Azul the most important stop-over site for this species in Bolivia. The reserve extension will protect five additional miles of short-grass river shore habitat used by Buff-breasted Sandpipers during their spring migration.

The Barba Azul extension protects more than 20 small isolated forest islands (including those shown above) which are preferred nesting and roosting sites for the Blue-throated Macaw. Photo by B. Hennessey, Asociación Armonía.

Also a haven for exotic mammals

Barba Azul is also a haven for mammals, thanks to the reserve’s protection of the Omi River, which is the only year-round source of water for miles around and a critical dry-season resource. The extension of Barba Azul improves its ability to protect the 27 species of medium and large mammals that depend on this habitat, including giant anteater (Vulnerable), pampas cat, puma, marsh deer (Vulnerable), pampas deer, white-collared peccary, and capybara. The reserve extension is critically important to maintain large protected areas for species needing expansive territories, like the maned wolf and jaguar.

The Beni savanna is an area twice the size of Portugal. It is a land of extreme contrasts, with intensive flooding in the summer and months of drought in the winter. Almost entirely occupied by private cattle ranches, these savannas have undergone hundreds of years of logging, hunting, and cattle ranching. Overgrazing, annual burning to promote new grass growth for cattle, and the planting of exotic grass species have greatly altered this ecosystem, which is now considered critically endangered.

Blue-throated Macaws fly free over the Barba Azul Nature Reserve. Photograph by D. Lebbin, ABC.Great result from exclusion of cattle, hunting, fishing logging of forest habitat

Frequent burning, overgrazing, and timber harvests within forest patches degrade habitat for Blue-throated Macaws and may limit the number and suitability of nesting sites. At Barba Azul, exclusion of cattle is already resulting in the restoration of forest understories, and artificial nest boxes offer hope that Blue-throated Macaws will have more opportunities to breed.

“When we originally purchased the Barba Azul Nature Reserve, it was a habitat that held high abundance of many animals. But once we removed cattle and stopped hunting, net fishing, logging, and uncontrolled grassland burning, the true destructive impact of an overgrazed, poorly controlled ranch could be seen. Everything is rebounding as if the area is recovering from a drought,” said Hennessey.

Macaw populations infamously affected by pet-trade and habitat destruction

The Blue-throated Macaw population has declined due to habitat degradation and trafficking for the pet trade. In addition to establishing the reserve, Armonía has worked with local communities in the Beni region to raise awareness of this species and effectively halt illegal trade in this macaw. Additionally, Armonía has provided local communities with beautiful synthetic feather head-dresses for use in traditional festivals as a conservation-friendly alternative to feathers gathered from wild macaws.

Birdwatchers flock to this haven

Barba Azul is a great place for birdwatchers, wildlife photographers, and researchers, who come from around the world to study birds and mammals based out of the research center on site. Armonía will be building additional cabins for tourists over the coming year. If you are interested in visiting the reserve, please contact BirdBolivia or find more information at ConservationBirding.org. More information about ABC and Armonía’s efforts to conserve the Blue-throated Macaw and Beni savannas is available on their websites.

NOTES

Original source of this article was http://www.abcbirds.org/newsandreports/releases/140102.html

American Bird Conservancy (ABC) is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit membership organization whose mission is to conserve native birds and their habitats throughout the Americas. ABC acts by safeguarding the rarest species, conserving and restoring habitats, and reducing threats, while building capacity in the bird conservation movement. We are proud to be a consistent recipient of Charity Navigator’s four-star rating.

Asociación Armonía is a non-profit organization dedicated to the conservation of birds and their natural habitat in Bolivia. Armonía’s conservation actions are based on scientific studies and active involvement of local communities, respecting their culture and knowledge. Asociación Armonía is the Bolivian key partner of American Bird Conservancy, BirdLife International, Loro Parque Fundación, Rainforest Trust, and World Land Trust.

Rainforest Trust is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization whose mission is to purchase and protect threatened tropical forests and save endangered wildlife through community engagement and local partnerships. For 25 years, Rainforest Trust has saved over 7 million acres of critical habitat across the tropics and consistently receives Charity Navigator’s top four-star rating.

Koala dies after paw in rabbit trap - Langwarrin, Victoria

The koala was rescued by Nigel Williamson of Nigels Animal Rescue. Barrie Tapp, the senior investigator for Animal Cruelty Hotline (sponsored by Animal Liberation NSW - free call 1800751770) was called in to investigate the trap issue. Jenny Bryant, of Koala Rescue, Tyabb, was also involved at the scene of the rescue and took the Koala to her rescue centre.

Sadly, despite Jenny's excellent care, the koala, which had had the trap hanging from its paw for days, died.

These traps are awful things and koalas these days, due to the removal of trees everywhere for human population growth, have to get down on the ground to go from tree to tree. They are slow on the ground and very vulnerable. They get stomped on by cows, attacked by dogs, and sometimes walk onto traps.

Victoria is not doing well in protecting wildlife or its habitat or our environment. Our wildlife carers work for no money and their services are hugely overstretched. Often, even when they successfully rehabilitate an animal, there is nowhere to release it because the native fauna habitat has been built over.

Getting help can be difficult

In this case, a complainant first called RSPCA and was told to call VicWildlife. He reported that, unfortunately, after calling three times, with no response, he called the local fire brigade, which in turn contacted Nigel.

Animal cruelty hotline is a free service to the community and you can remain anonymous if you so wish to report a complaint regarding animal abuse/cruelty. Animal cruelty hotline is not in any opposition to any other animal welfare organisation but is an alternative with trained investigators. Barrie Tapp an ex RSPCA Senior inspector for some two decades heads the Vic division and works closely with RSPCA Vic/ Vicpol/ and DEPI.

Stop the Pilliga Forest coal seam gas mining

Really informative video inside, beautifully put together by trevorjbc, containing a variety of knowledgeable speakers in the field, and showing the landscape. Farmers and environmentalists don't want CSG mining, but the government is likely to face a backlash from the minerals sector unless it acts. Critics fear that fracking not only opens up cracks in the coal seam, but could also result in gas escaping into drinking water as it rises to the surface. It would be economically reckless and short-sighted for the supply of CSG to destroy valuable farmland, and compromise underground water supplies. There are fears from some landholders that the ban in Victoria will be lifted. (This article has been adapted from a comment).

Really informative video inside, beautifully put together by trevorjbc, containing a variety of knowledgeable speakers in the field, and showing the landscape. Farmers and environmentalists don't want CSG mining, but the government is likely to face a backlash from the minerals sector unless it acts. Critics fear that fracking not only opens up cracks in the coal seam, but could also result in gas escaping into drinking water as it rises to the surface. It would be economically reckless and short-sighted for the supply of CSG to destroy valuable farmland, and compromise underground water supplies. There are fears from some landholders that the ban in Victoria will be lifted. (This article has been adapted from a comment).Coal seam gas is a fossil fuel that is almost entirely made up of the greenhouse gas, methane. It's feared that large tracts of farmland will become unavailable for food production, forests and native bushland will be cleared and fragmented.

According to the industry, developing new supplies is absolutely critical if Australia wants to put downward pressure on energy prices. However, the gas industry want to drill more and more wells to meet their lucrative export contracts, and our prices will be linked with the much higher Asian market.

If it comes to a choice of harvesting underground coal seam gas, until it expires, or the long term integrity of our land, food and water supplies, then it would be counter-productive to prioritise the former over the latter.

The Pilliga is a vast expanse of bushland, located between Narrabri and Coonabarabran in western NSW. This iconic area of public land is under threat from the largest coal seam gas project ever proposed for New South Wales.

The Wilderness Society has been most concerned about the possible impact on the Pilliga forest and Channel Country region of Queensland's Cooper Basin. The government is prepared to relax environmental laws, or "green tape", for gas exploration.

Pilliga forest home to many threatened species, including the koala, Pilliga mouse, superb parrot and southeastern long-eared bat and regent honeyeater. A new ecological study of the Pilliga Forest in north-west NSW has found it is a “Noah's Ark” or refuge for many bird and mammal species that are declining across Australia.

Santos says it believes its CSG operations in the Pilliga can supply 25 per cent of the state's gas needs. More than 54% of Australia is covered by coal and gas licences or applications, and its clear that mining companies are riding roughshod over our governments and local communities. Dead animal bones in the bottom of a coal seam gas wastewater pond, according to the Stop Pilliga Coal Seam Gas movement,

The NSW government gave approval for the drilling in the woodlands in eastern Australia under stringent environmental conditions. The NSW government is hoping that a successful development by Santos of its coal-seam gas development in the Pilliga Forest in the northwest of the state will both satisfy some of the state's energy needs and demonstrate that coal-seam gas is not as environmentally harmful as its opponents claim.

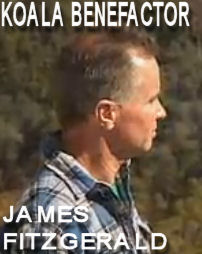

Private trust land set aside for koala comeback by James Fitzgerald in A.C.T. - video

For all you depressed wildlife battlers out there, here is a truly 'good news' koala story about a wildlife warrior hero, James Fitzgerald, who has placed nearly 800ha of what looks like good sub-alpine land in trust for koalas. Even better, the koala population there turns out to have strong new genetic properties and is chlamydia free!

For all you depressed wildlife battlers out there, here is a truly 'good news' koala story about a wildlife warrior hero, James Fitzgerald, who has placed nearly 800ha of what looks like good sub-alpine land in trust for koalas. Even better, the koala population there turns out to have strong new genetic properties and is chlamydia free!

The ABC has done a great job in this news report, giving good background and great photography and letting the world know about this wonderful public servant who, in his private time, has made such a difference for one group of koalas.

Contrast this with the position of Queensland koalas, made so tragic by a succession of vandalistic governments, of which the most recent Newman government really seems to be officially in favour of pack-raping this land. (See "KoalaTracker Design Competition to help save koalas"

Then again, these 800 ha set aside by James Fitzgerald are not a government initiative. If wildlife protection were left to governments, we would have no reserves. It is a fight, a continual fight, but James Fitzgerald has made a big advance on the enemy in the ACT. Good on him!

The Moral Lives of Animals by Dale Peterson - Book Review

Dale Peterson begins his thesis with the execution of elephants for crimes of murder against humans. An unusual, well-argued and inspiring book. Peterson co-authored the famous Demonic Males, an anthropological study in their own environment of several kinds of apes, including humans. I expected him to come up with something new on the subject of animal morality, and I was not disappointed. This is a real thesis, a slow burning one that reaches a high temperature.

Dale Peterson begins his thesis with the execution of elephants for crimes of murder against humans. An unusual, well-argued and inspiring book. Peterson co-authored the famous Demonic Males, an anthropological study in their own environment of several kinds of apes, including humans. I expected him to come up with something new on the subject of animal morality, and I was not disappointed. This is a real thesis, a slow burning one that reaches a high temperature.

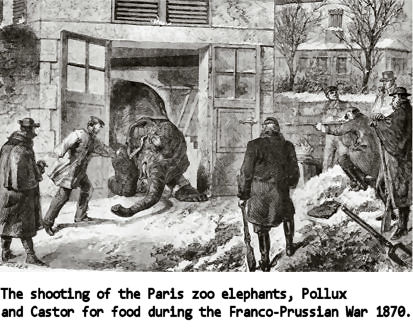

Dale Peterson begins his thesis with the execution of elephants for crimes of murder against humans. He thus arrests our attention with a couple of concepts most of us probably don't mull over every day in relation to elephants: 'execution' and 'murder'.

Execution and Punishment

Firstly, he calls to our minds the difficulty of killing an elephant and of how authorities 'execute' elephants mostly when those animals have done something that makes them seem pretty dangerous - generally maiming or killing a human. The level of decision-making and authority to kill the elephant in question is such that it takes on the character of an execution and a punishment.

Then he introduces the concept of 'murder' by non-humans of humans. He shows how people in earlier times have tended to assume intent and deliberation in animals and that, even though this assumption has been largely dropped with the institution of Cartesian values that say animals are machines without feelings, with elephants people tend, despite themselves, to assume intelligence and planning.

Australians might recognise the motif of execution and murder in the way we sometimes deal with sharks and crocodiles after one of them has killed one of us. And then, there is our attitude to dingos. And pit-bulls.

Speciesism

An important part of Peterson's logic depends on establishing that most species think of themselves as the most important, possibly the only 'real' species, just as humans do. He gives an example of how, when human observers were educated not to interact at all with non-human apes in the Goodall studies - the non-human apes simply forgot the human apes were there. They accommodated their presence in the sense that they went around them, but the almost never attempted to interact. Humans went off their radar - just as most other species are nearly always off most humans' radars.

Obviously you have to read the book to understand what Peterson is talking about here. He is sufficiently original to surprise most people saturated in animal ethology, evolution and animal rights literature.

Empathy a widespread evolutionary trait

Species self-centredness does not exclude a capacity for empathy when there is meaningful interaction with another species and within one's own. Peterson defines empathy and argues very effectively that this is an evolutionary trait shared by many species apart from humans. Readers may not be surprised by this observation, but they will probably be impressed by the reasoning and examples.

With this significant beginning, Peterson goes on to examine other perspectives on animals in laboratories and in the wild which many of us won't have thought of. He also has a lot of unusual but well documented examples from the wild, in part due to his long association with Jane Goodall.

Emotional attitude

When I was deliberating about buying this book, I wondered how Peterson would deal with his own emotions on these subjects and with those he might expect in a reader. Emotional attitude is very important in such works because it can put readers off for a number of different reasons. For instance, some readers might seek to avoid the pain of knowing of awful treatment of animals. Conversely, animal rights readers might suspect an author who did not express indignation and anger. On the other hand, scientific readers and people used to repressing their emotions might prefer an absence of emotion. How does Dale Peterson deal with this? He doesn't become 'emotional' but he nonetheless validates the experience of animals by describing their reactions - for instance how laboratory rats would go hungry and even risk starvation to avoid imposing pain on their rat-neighbours when that was a risk entailed in seeking food - for instance where pressing a lever to get a pellet of food appeared to cause another rat to receive some kind of 'punishment'.

Does Peterson rail against the people who would deliberately cause animals - from lab rats to chimpanzees and elephants - pain? No, he doesn't. But the actions of the animals to protect each other dignify the animals themselves, and so the reader makes their judgement.

Peterson succeeds here in a very difficult field: he teaches us that the matter is too serious for mere indignation. Serious in a manner that requires intense reflection on our relationship with other creatures, with ourselves and each other.

Whales

"The puffin (harvested locally, the waitress promised) was sliced thin, its gaminess muted with litchi and fig. The minke whale, also finely carved, tasted like beef tenderloin with a faint metallic finish; it was savoury and delicate when paired with an airy washabi cream." (Liz Alderman, New York Times travel journalist, 2013)

The industrialized killing of whales during the twentieth century was 'perhaps the most callous demonstration history offers of humankind's self-appointed dominion over animals. One searches almost in vain for an expression of sympathy, compassion, understanding, or rationality. In their place were only insensitivity and avarice.' (Richard Ellis,2003. The Empty Ocean).

Whales are present throughout the book, an undercurrent in the form of educated interpretations of Moby Dick, which will absolutely fascinate anyone who has studied it, but the cetaceans surface, so to speak, in their full glory, in the last chapter.

Now I am not one to be impressed by interspecies comparisons with human intelligence because I don't think I judge other species' worth in relation to humans. I have therefore never been very taken by the popular iconology of whales and porpoises. I love the sea and enjoy the creatures in it. They are a whole other planet. They do not need to be like me for me to want them to be.

Whaling on the west coast of Australia

No, when I think of whales, I think about how, when I was a child about five years old I participated in one of the last whale hunts off the West Australian coast. Two whalers were involved - one Australian and one Russian. My father (a scientist) was a guest for the day on the Russian boat and my mother and I were on the Australian one. The two boats competed for a mother whale and her calf. The Russians caught the mother and the calf. It was windy. The sea was roiling. The whales, although huge, appeared and disappeared among the waves. I remember the excitement of the pursuit and apparently friendly competition between the boat crews pursuing the same whale.

When we came ashore, we left the real crews to deal with their catch and drove to the country pub where we were sleeping.

Early the next morning we returned to the whaling station, eager to see the work that had been done. We climbed up on a rise above the station and looked down into a bay like a pit between cliffs. Our stomachs lurched at the sight. Humans were climbing over the partially exposed skeleton of the huge mother whale in a scene that resembled one of Hieronymous Boch's versions of hell. They were hacking away at the giant creature like ants with axes and knives. Was the little one lying beside its mother? I cannot be sure of my memory. I do remember that even my father (a man who made his own spears for underwater fishing) lost his bullish enthusiasm for the scene. The terrible smell of rotting whale even outdid the visual desecration of such an obviously monumental animal. Above everything else, the smell drove us away, gagging with horror, suddenly deeply depressed.

I was glad when I became aware they had banned whaling some years after that. Since then I have enjoyed the sight of whales with the feeling that - at least those I can see in Australia - are not menaced by a local whaling industry. Since there are already so many people out there protesting on behalf of whales, with an apparent appetite for associated posters and films, I have felt I could choose to spend my time trying to defend our very deserving Australian indigenous land-creatures and vegetation, which lack the profile in their own country that whales do, but suffer similarly.

Whale statistics

Reading Dale Peterson's last chapter, however, concentrated my mind on the precarious position of whales. Peterson doesn't waste the reader's time with excess adjectives and examples. He makes the matter perfectly clear. Some whale populations that recovered from initial whaling bans are now nearly extinct, largely due to the current activities of the Japanese, the Greenlanders and the Icelanders. Some of the biggest creatures on the earth - with much larger brains than ours and similar neuronal connections - and perhaps with superior morality and values - are close to being wiped out by a bunch of badly-educated apes who no longer are in touch with what is going on around them. There is no excuse for whaling. There is no excuse for extinction. We have no excuse, except perhaps that, collectively, we humans are not as smart as we think.

"Altogether the brains of cetaceans show 'a structural complexity that could support complex information processing, allowing for intelligent, rational behavior.' That's the word from the neuroanatomists, and those scientists who have been studying cetacean behavior for the last several decades strongly support it, finding a group of animals who have excellent memories and high levels of social and self-awareness, who are excellent at mimicking the behavior of others and can respond to symbolic representations, who form complex and creatively adaptive social systems, who show a broad capacity for the cultural transmission of learned behaviors ... and so on."

"Nearly half of the thirteen great whale species are currently listed as endangered, some critically so, while a number of localized populations are gone or just about gone. The right whale of the North Atlantic, once common, is now down to a population of around three hundred and still declining. These giant animals were given their name in the old days because, as slow-moving and naturally-buoyant-after-death creatures, they were the 'right' ones to find and kill. Now they are right for extinction, with their continuing decline today, largely the consequence of accidental collisions with ships. The magnificent blue whales of the Antarctic, abundant until whalers discovered them, have been reduced to around 1 percent of their original numbers. At more than a hundred feet long and 150 tons heavy, incidentally, these animals are the largest creatures ever to have lived on this planet, land or sea, but they, too, are teetering on the edge of nonexistence. Also endangered or threatened are the gray whales of the northwestern Pacific, the fin whales, the sei, the beluga, and the sperm whales. 'Trusting creatures whose size probably precluded a knowledge of fear,' writes author and marine wildlife expert Richard Ellis, in The Empty Ocean (2003), 'the whales were chased until they were exhausted and then stabbed and blown up; their babies were slaughtered; their numbers were halved and halved again.' The industrialized killing of whales during the twentieth century, Ellis concludes, was 'perhaps the most callous demonstration history offers of humankind's self-appointed dominion over animals. One searches almost in vain for an expression of sympathy, compassion, understanding, or rationality. In their place were only insensitivity and avarice.'

"The International Whaling Commission (IWC) was originally organized in 1946 to support the industry by promoting the supposedly 'sustainable' harvesting of whales. But commercial whaling had, by the second half of the century, reduced the numbers of most species so decisively that in July of 1982 the IWC declared a moratorium on all whaling.That important and positive event has been challenged continuously by the Starbucks[1] of this world. The Soviet whaling industry simply continued harvesting whales of all species, all ages and sizes, while falsifying their reports. The Japanese officially adhered to the terms of the moratorium by identifying their whaling as 'scientific' rather than a commercial enterprise. Iceland ignored the moratorium, allowing its ships to kill one hundred minke whales and as many as one hundred and fifty endangered finned whales during the 2008 and 2009 seasons. The Norwegians have never stopped whaling either and continue to slaughter hundreds of minke whales yearly, insisting that whale killing is a glorious part of their cultural heritage and, furthermore, that these giant mammals eat too many fish. During the 2009 meeting of the IWC, meanwhile Greenland,backed by the Danish government, applied for permission to harvest as many as fifty endangered humpback whales over the next five years for the purposes of 'aboriginal subsistence,' even though Greenland already has a surplus of whale meat, which is sold in supermarkets."

Exotic eating driving extinction everywhere

After I began writing this review, I was sad to read the following in an internationally syndicated travelogue by New York journalist, Liz Alderman, about Iceland nightlife:

"We studied the menu and pointed to the puffin and minke whale appetisers, Icelandic delicacies. The puffin (harvested locally, the waitress promised) was sliced thin, its gaminess muted with litchi and fig. The minke whale, also finely carved, tasted like beef tenderloin with a faint metallic finish; it was savoury and delicate when paired with an airy washabi cream."

Liz Alderman was not starving, was not an indigenous hunter, was not unable to procure other kinds of food, so how could she be so blind and deaf and dumb to the imminent extinction of the whale and the puffin?[3] And, if it sold articles, would she also sample elephants' tusks and tigers' bones? Where would she draw the line? Would she, could she draw a line anywhere?

Is there any hope for the world? Are we any different from the Ancient Romans who gorged themselves with rare animal dishes and self-induced vomiting so as to be able to eat more?

It is as if every local rule that ever developed to save something for later and maintain the populations of food sources is being eroded by marketing for short-term gain to nations of unhappily fat people who cannot avoid exposure to the brainwashing.

I know I am not the only one who is absolutely sick of the multiplication of cooking shows on television. I rarely turn on my own television, but television is now everywhere - on the back of airline seats, in hospitals and doctors' waiting rooms, in public squares. It is a form of ideological pollution. At every hour of day and night we are sold the idea of eating more and more kinds of animals, to seek the out wherever they may hide and popularise their demise. So we are supposed to admire a man who urges us to taste fried spiders, then follow the camera's eye as it roves greedily over other produce, passing casually over the sad little face of a small dead bat. The image haunts me still, because I have actually been friends with a bat. I recorded it in this film, Gracie, the flying fox.

Julia Buch, who introduced me to the friendly bat took to saving baby bats orphaned on bat hunts in New Guinea, when she was a child. A tradition of bat eating among a small population of New Guinea clans-people is one thing; 7.5 billion people hunting down every bat and every spider, every tasty rare plant and turning their habitats into fields for soy and corn is like some kind of scary nightmare. Yet that is what is happening! Humans have become the nemesis of every other creature in the world. Our behaviour is monstruous.

NOTES

[1] Starbuck was one of the characters in Moby Dick. He was less impressed by Moby Dick and Captain Ahab than most of the crew. He wanted to get on with business and go home to his wife.

[2] Liz Alderman, "The nights and lights of Reykjavik," Australian Financial Review, February 22-24, 2013, pp22-24.

[3] Puffins are hunted for eggs, feathers and meat. Atlantic Puffin populations drastically declined due to habitat destruction and exploitation during the 19th century and early 20th century. They continue to be hunted in Iceland and the Faroe Islands.

The Atlantic Puffin forms part of the national diet in Iceland, where the species does not have legal protection. Puffins are hunted by a technique called “sky fishing”, which involves catching low-flying birds with a big net. Their meat is commonly featured on hotel menus. The fresh heart of a puffin is eaten raw as a traditional Icelandic delicacy.

Conservation

SOS Puffin is a conservation project based from the Scottish Seabird Centre at North Berwick to save the puffins on islands in the Firth of Forth. Puffin numbers on the island of Craigleith, once one of the largest colonies in Scotland, with 28,000 pairs, have crashed to just a few thousand due to the invasion of Tree Mallow, an exotic plant which has taken over the island and prevented the puffins from accessing their burrows and breeding.[21] The project has the support of over 450 volunteers and progress is being made with puffins returning in numbers to breed this year.

In the summer, children in Iceland walk around local areas with boxes and containers to rescue puffins that land in dangerous spots, such as close to cities, where the city light has confused them into trying to fly into that direction, as opposed to diving in the direction of the light reflecting off the sea water near their burrows. The children who rescue puffins then later release them at sea, and away from the city. Source: Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Puffin

About the author of this review

Sheila Newman is an evolutionary sociologist. Her home page is http://candobetter.net/SheilaNewman Her most recent book is reviewed at /?q=node/3155. See below for where you can obtain a copy.

Julianne Bell, PPLVic: Citizens rights to preserve public land and wildlife habitat from private greed in Melbourne Planning

This superb document establishes a history of concerted public demand for protection of the green wedges and a host of reasons for that public opposition to Matthew Guy's six new suburbs. It represents more than 80 groups of Victorians - (Ed. Candobetter.) "The whole rationale for extending the Urban Growth Boundary is to accommodate the unprecedented flood of population to Victoria. PPL VIC considers that the extension of the Urban Growth Boundary is really the thin end of the wedge. As there are no plans to stop the present high rate of population growth (mostly from immigration) the process of loss of Green Wedges and agricultural land is endless. There will be another extension when the proposed boundaries are seen to be filling up. The Government must abandon the Green Wedge land grab as destructive of the environment, a threat to wildlife, including endangered species, and as a major contributor to Green House Gas Emissions. Around the urban fringe we have a concentration of some of the most endangered eco- systems in Australia..." Julianne Bell, Protectors of Public Land, VictoriaJulianne Bell, Protectors of Public Land, Victoria.

This superb document establishes a history of concerted public demand for protection of the green wedges and a host of reasons for that public opposition to Matthew Guy's six new suburbs. It represents more than 80 groups of Victorians - (Ed. Candobetter.) "The whole rationale for extending the Urban Growth Boundary is to accommodate the unprecedented flood of population to Victoria. PPL VIC considers that the extension of the Urban Growth Boundary is really the thin end of the wedge. As there are no plans to stop the present high rate of population growth (mostly from immigration) the process of loss of Green Wedges and agricultural land is endless. There will be another extension when the proposed boundaries are seen to be filling up. The Government must abandon the Green Wedge land grab as destructive of the environment, a threat to wildlife, including endangered species, and as a major contributor to Green House Gas Emissions. Around the urban fringe we have a concentration of some of the most endangered eco- systems in Australia..." Julianne Bell, Protectors of Public Land, VictoriaJulianne Bell, Protectors of Public Land, Victoria.

The superb document below establishes a history of concerted public demand for protection of the green wedges and a host of reasons for that public opposition to Matthew Guy's six new suburbs. It represents more than 80 groups of Victorians protesting against Victorian government population growth and development policies for reasons that damn Matthew Guy's extension of the Urban Growth Boundary. These extensions are even worse than those planned by the preceding government, however the preceding Kennett, Bracks and Brumby Governments created the planning precedents and undemocratic conditions that give the Baillieu Government the delusion that it has the right to ride over citizens rights' to conserve public land and wildlife habitat from private greed.

Protectors of Public Lands Victoria Inc.

Mr George Seitz

Committee Chair

Outer Suburban/Interface Services & Development Committee

C/- Parliament House

Spring Street, Melbourne

VIC 3002

19 October 2009

Dear Mr. Seitz,

Submission to Parliamentary Outer Suburban Interface/Services and Development Committee Inquiring into the Impact of State Government Decision to Change the Urban Growth Boundary

Introduction:

I am making a submission on behalf of Protectors of Public Lands Victoria Inc. (PPL VIC.) I should by way of introduction mention that our organisation, established in 2004, is a State wide coalition of over 80 environment, heritage, resident and parks groups across Victoria. We are dedicated to keeping public lands in public hands and to protecting and conserving iconic heritage places and environmental sites of significance.

Summary of Grounds of Opposition: In addressing the terms of reference we are considering

“The impact of the State Government’s decision to change the urban growth boundary on landholders and the environment…”

PPL VIC draws the Committee’s attention to the failure of the State Government in strategic urban planning over the last 10 years and in encouraging uncontrolled entry of settlers to Victoria without examining sustainable population levels. We object to creation of growth areas outside the existing boundaries as extending and creating urban sprawl; alienation of established Green Wedges; destruction of the environment and wildlife; loss of biodiversity; creation of “dormitory” settlements without infrastructure and services; likely social alienation of youth; loss of arable land for food production; increasing car dependency; worsening Victoria’s greenhouse gas emissions and contributing to climate change with land clearance, unsustainable housing and reliance on road transport; plus knowingly approving the building of new settlements in fire-prone areas. Additionally we deplore the imposition of a vendor tax on landowners in order to fund the infrastructure of the new settlements and the impetus given to land speculation and “land banking.” PPL VIC supports the submissions made by our colleagues from the “Green Wedges Coalition” and “Taxed Out”.

The grounds of our submission are as follows:

New Growth Areas = Future Urban Sprawl = Major Failure of Strategic Urban Planning:

The Bracks Government guaranteed in 2002 that, under a Labor Government there would be no changes or amendments to the Urban Boundary or to the Green Wedges corridors. The fact that there are now radical changes represents a serious breach of faith with the electorate by the Brumby Government. Melbourne 2030 was considered to be the blue print for future development and was expressly intended to contain future urban sprawl; to prevent urban incursions into rural land; to concentrate residential growth into areas served by high capacity public transport; and protect sensitive environmental zones around the city. Many planners have pronounced Melbourne 2030 dead in view of recent radical departures from the plan.

Before the 2002 election the State Government announced protection of Melbourne’s green wedges from subdivision and inappropriate urban uses. There was bipartisan support - the Opposition supported the green wedge protection legislation when it passed through the Legislative Assembly before the 2002 election.

The Government has additionally broken a 2005 promise when 11,500 hectares was excised from Green Wedges land that there would be no further changes until 2030. The community accepted the excision on this proviso. Apparently, the Minister for Planning gave a number of assurances right up to the announcement of the review of the Urban Growth Boundary that there would be changes to Green Wedges. .

The State Government announced its review of the Urban Growth Boundary in December 2008 when it released the Melbourne @5 million, an update to Melbourne 2030: Planning for Sustainable Development. This signalled the State Government’s plans to open up at least 23,000 hectares – including land in Green Wedges areas - for urban expansion to allow for construction of 600,000 houses with 284, 000 of these to be located in growth areas. It was only apparently belatedly realised by Government advisers and planners that Victoria needs to accommodate another 1 million people before 2025. By 2036 Melbourne is predicted to have a further 1.8 million, twice the number forecast by Melbourne 2030 planners. By anyone’s reckoning failure to predict this massive population boom is a monumental blunder in strategic planning (See also comment under population)

We can see no improvements under the current Delivering Melbourne’s Newest Sustainable Communities (DMNSC) report on the Urban Growth Boundary Review released in June 2009. PPL VIC was alarmed to see that according to the Green Wedges Coalition the report proposes to excise a further 41,663 hectares from Melbourne’s Green Wedges, nearly twice the area estimated to have been needed in last December’s Melbourne @ 5 Million report.

Minister Madden has added to proposals by announcing on 6 October 2009 that new “Precinct Structure Plans guidelines” were to be added, a kind of overlay for suburbs of 3,000 dwellings or more. These guidelines were drawn up to try to ensure developments avoided becoming isolated, so called “dormitory” suburbs - places where there is nothing to do but sleep. The Age article of 11 October 2009 “Sprawl of the wild,” by Melissa Fyfe says “

The Victorian Government has discovered sustainable communities. Pity it’s 10 years late.”

On 16 October 2009 Planning Minister Madden announced the draft legislation for Growth Areas Infrastructure Contribution Bill. We have only been given time to make comments until 2 November 2009. (It is not known if the legislation will be introduced to Parliament before this Committee has reported.) The problem is that arrangement to levy the GAIC have been changed or significantly amended. Michael Hocking of Taxed Out says on his website:

“This is taxing the landowner by stealth. The tax is still applied at a flat rate regardless of the sale price yet the land may be twenty years from development. A property owner needing to sell in the short-term will find it virtually impossible to find a purchaser who is prepared to accept a GAIC liability when he sells, meaning the only likely purchaser is a developer not interested in the value of the dwelling and not interested in paying development prices for land that won't be developed for decades. The Growth Areas Authority assumptions relating to value uplift remain fundamentally flawed and Taxed Out Inc. intends to expose these issues at the Parliamentary Inquiry…In many respects this situation is worse than that originally proposed.

PPL VIC deplores the fact that the State Government appears to have attempted to mislead affected landowners. We also point out that this debacle over changes to the GAIC further illustrates that our contention that this is planning on the run.

What is a Sustainable Population for Victoria?

The whole rationale for extending the Urban Growth Boundary is to accommodate the unprecedented flood of population to Victoria. It is instructional to Google the “Population Clock” of the Bureau of Statistics. This shows the resident population of Australia which increases by one person every 1 minute and 12 seconds. This projection is based on the estimated resident population at 31 March 2009 and assumes growth since then of:

• one birth every 1 minute and 44 seconds,

• one death every 3 minutes and 39 seconds,

• a net gain of one international migrant every 1 minutes and 53 seconds leading to

• an overall total population increase of one person every 1 minute and 12 seconds

PPL VIC considers that the extension of the Urban Growth Boundary is really the thin end of the wedge. As there are no plans to stop the present high rate of population growth (mostly from immigration) the process of loss of Green Wedges and agricultural land is endless. There will be another extension when the proposed boundaries are seen to be filling up.

The extension of the Urban Growth Boundary does not save private or public open space in the established suburbs - the rate of population growth is so high that Melbourne is getting more urban densification daily as well as urban sprawl. As we have pointed out the State Government is devoid of coherence in these planning matters and its approach to endless population growth.

PPL VIC considers it imperative that the Victorian Government hold a forum to determine the population sustainable for Victoria, especially in view of water shortages and the likelihood of future droughts. (Excuses used have been “immigration is a Federal matter” but State Premiers have influence in Canberra.) At a rally on 14 July 2009 protesting over Planning Minister Madden’s “Cash for Chat” with developers, PPLVIC and allies delivered a set of resolutions to the Minister including the need for a population forum. There were over 500 people at the Rally which indicates the strength of public feeling concerning the issues raised here.

I have a quote here from Mr Kelvin Thomson MHR, Federal Member for Wills who says that:

Everything that makes our city the great place to live, work and raise a family, is potentially under threat if population growth and urban sprawl continue at the current rate. We must implement a strategy to control population growth, urban expansion and development. Our way of life, open spaces and infrastructure cannot be sacrificed on the altar of ever expanding population. We have a responsibility to secure our city’s future by thorough, thoughtful and detailed planning. This planning should not include an expanding Melbourne waistline.” (“Five Million is too many: Securing the Social and Environmental Future of Melbourne” Submission to the Urban Growth Boundary Review July 2009.

Destruction of the Environment and Green Wedges:

The Government must abandon the Green Wedge land grab as destructive of the environment, a threat to wildlife, including endangered species, and as a major contributor to Green House Gas Emissions. Around the urban fringe we have a concentration of some of the most endangered eco- systems in Australia including the Western Basalt Plains Grasslands and Grassy Woodlands in the Darebin, Jackson and Merri Creek valleys, with 400 year-old red gums, and plus loss of habitat for a range of threatened species (e.g. Southern Brown Bandicoot.) PPL VIC supports the submission of the Green Wedges Coalition as being an excellent detailed statement of the threats to significant landscapes, endangered species and wildlife plus indigenous vegetation.

The 15,000 hectares of grassland reserves to be provided over 10 years as a trade-off for grasslands is apparently of poorer quality than the kangaroo (themeda) grasslands to be destroyed

The removal of environmental protection from all areas within the Urban Growth Boundary would seem to indicate that areas such as significant parts of the Merri Creek Catchment will not be protected from environmental damage or even clearing.

Areas for development are clear felled by developers. The loss of trees and other vegetation for housing adds to global warming effect. Is there any provision for conservation?

The proposed high density, low open private space in these outer suburbs means they will be hotter - urban heat island effect - from the lack of the cooling effect of vegetation/transpiration - low ratio of vegetation to concrete and other hard surfaces.

What provision is made for public open space? There is no mention made of public open space for passive recreation as well as sports fields and recreation areas.

On past performance, no allowance will be made for wildlife in outer suburban development. PPL VIC has had experience with kangaroos of Somerton and Morang where animals get trapped in developed areas and just left to get killed on roads. The outer suburban interface is considered terra nullius it seems. What of smaller animals/birds what about the grasslands and inhabitants? There appears to be no consideration given to the creation or maintenance of wildlife corridors.

The State Government appears to have taken little notice of report by the Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability, Mr Ian Mc Phail, in “The State of the Environment Victoria 2008”. In it he comments:

"Victoria's population growth, increasing affluence and the expansion of our cities and towns has contributed to unsustainable levels of resource consumption and waste production. This has direct environmental impacts through changes in land use from conservation and agriculture to cities and towns. To supply our cities and towns, we harvest water for residential and manufacturing purposes, changed river flows, discharge wastes to land and sea, remove native vegetation and send damaging gases into the atmosphere." (Refer in the report to A Culture of Consumption. Drivers of Change – Population, Change and Settlements Page 9)

The report continues:

“Continuing growth of Victoria’s population will increase demand for land, as well as housing and transport services, potentially leading to more waste and pollution. Extra demand for water is particularly pertinent given the predictive effects of climate change on already depleted water storages.”

Mr Mc Phail concludes on a depressing note:

"It is currently cheaper to protect the environment to than to restore it but it is even cheaper to degrade it…”

Urban Growth Areas in Fire Prone Areas:

Whether it is advisable settling thousands of people in outer suburban fire prone areas does not appear to have occurred to the Government. These are the outer suburban areas classified as "Growth Areas": Beveridge, Bulla, Devin Meadows, Cranbourne East, Clyde North, Diggers Rest, Donnybrook, Kalkalo, Melton, Mt Cottrell, Officer, Pakenham, South Morang, Sunbury, Tarneit and Truganina.

Councils opposed to the extension of the Growth Areas Boundary and the imposition of the Growth Areas Infrastructure Contribution are Melton, Casey, Cardinia and Mitchell. Wyndham refuses to comment.

It is apparent that these areas are either under resourced by fire services or not serviced at all. We assume this also goes for ambulance and police. Would the State Government be liable if fire services were not provided and a fire went through the settlement?

The Age reported on 4 July 2009 (Lessons to Learn) on the proceedings of the Bushfire Royal Commission and pointed to urban sprawl as one of the “fatal confluence of factors” that led to Black Saturday.

Cost to Victorians:

The cost of building new homes in the rural fringes of Melbourne is double that of constructing infill dwellings in the inner city. This is the hidden cost of suburban sprawl. This is an unacceptable financial burden for Victorian tax payers to shoulder. The added costs include extra infrastructure such as power, water and transport, as well as higher health costs and greenhouse gas emissions.

The report, commissioned by the State Department of Planning and released in July, cites research that found

"for every 1000 dwellings, the cost for infill development (in existing suburbs) is $309 million and the cost of fringe developments is $653 million".

It has been stated by Minister Madden in Parliament (and reported in the Sunday Age 11 October that the funds to be raised by the $95,000 hectares Growth Areas Infrastructure Contribution will cover only 15 per cent of total infrastructure costs. The Minister is prepared to sacrifice Green Wedges land that makes Melbourne “livable” and to destroy the livelihoods of many small landowners and farmers for this minor financial return.

Unfair Tax on Land Vendors: The Growth Areas Infrastructure Contribution is an unfair, discriminatory tax on family farms and small landowners, even after amendment by the State Government in draft legislation. As we have consistently maintained, the tax needs to be withdrawn and any charges levied at the point of development, consistent with the approach taken in other Australian states. PPL VIC supports the campaigns of “Taxed Out” and as mentioned above held a joint rally on 14 July 2009 to protest against the Growth Areas Infrastructure Contribution.

Perpetuation of Car Dependency: The plans to construct major freeways/ring roads and the absence of plans for extensive rail networks to serve the new suburbs spells out that the population of Melbourne will remain dependent on cars despite the uncertain future of oil. We are particularly concerned over plans to build the E6 freeway through Woollert. The roadway appears redundant.

Reduction of Arable Land: Given our population crisis and likely food shortages with the drought it is unthinkable that the Government can even be contemplating turning over arable land for housing development. The loss of vegetable farms including prime market garden land in the Westernport Catchment will increase food miles for our produce.

Increase of Green House Gas Emissions: Climate change is the most important moral question of the age and must be at the forefront of our public policy. The State Government appears to have its head in the sand. Compared to other cities in the world Melbourne has one of the highest rates per capita. Our private vehicles and public transport were recently recorded to generate 11 million tonnes of carbon monoxide a year compared with 8.5 tonnes in London. The increase in urban sprawl will worsen our figure.

Accommodation of Population within Existing Urban Growth Boundaries:

No examination has been undertaken of how the increased population can be accommodated in Metropolitan Melbourne.

Suggestions have been made that an inventory should be conducted of development applications which have already been approved by Council within the Urban Growth Boundary but which have not yet been built. Utilizing existing approvals might go some way to addressing the issue.

An inventory also needs to be undertaken of brown field sites and land which could be available for residential development – former transport depots, rail sidings and Commonwealth Government sites eg the Maribyrnong Defence site.

It is most unfortunate that the practice of “land banking” by developers appears widespread throughout the city. Take for example land on the former Royal Park Psychiatric Hospital site in Parkville which was given to Australand and the Citta Property Group to build a residential development then used for 2 weeks for the 2006 Commonwealth Games Village. The original plans showed a wall of 700 units in a 9 storey block along City Link. The land is still vacant and there have been no attempts to commence building. The developers are said to be waiting until the “market is right.” The truth is that developers prefer green field sites and are unwilling to invest in developing brown field sites.

Request to Committee: PPL VIC urges the Committee to reject approval of the extension of the Urban Growth Boundary and the iniquitous Growth Areas Infrastructure Contribution and to develop recommendations for accommodating increased population within the Urban Boundary plus arriving at consensus for determining a sustainable population for Melbourne.

Yours sincerely

Julianne Bell

Secretary

Protectors of Public Lands Victoria Inc.

P) Box 197

Parkville 3052

0408022408

jbell5[AT]bigpond.com

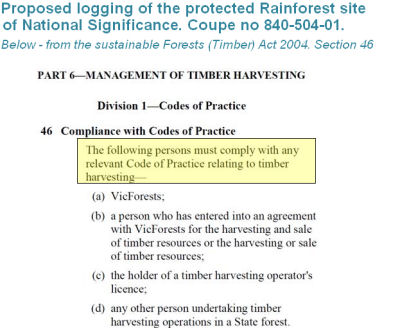

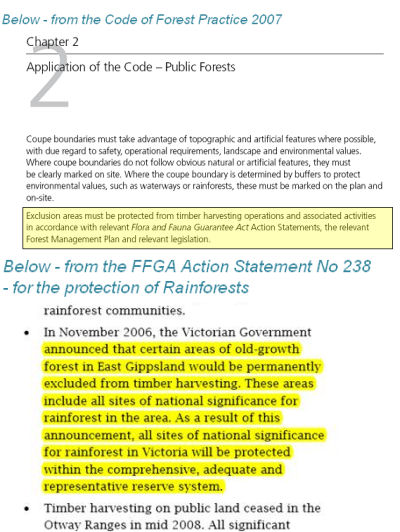

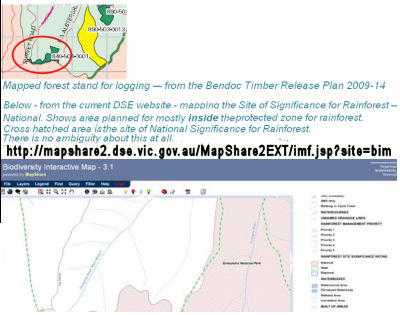

Stop Press! Legal injunction to stop Victorian rainforest logging - EEG leads the others - again!

VicForests up before the Supreme Court - again - for alleged illegal logging, thanks to the amazing avatars of Environment East Gippsland. Dig into your pockets, folks! EEG does more for you than your taxes!

VicForests up before the Supreme Court - again - for alleged illegal logging, thanks to the amazing avatars of Environment East Gippsland. Dig into your pockets, folks! EEG does more for you than your taxes!

Wednesday 14th December 2011

VicForests is again being sued in the Supreme Court over what an environment group believes is illegal logging of a very significant protected rainforest area. Environment East Gippsland, which successfully sued VicForests last year, is lodging papers for an urgent injunction this morning in the Melbourne Supreme Court to stop the logging.

“This is the third case of what we believe is illegal logging that VicForests will have to answer for”, said Jill Redwood, coordinator of the group. “The public thinks this type of lawless destruction of protected primary forest and rainforest only occurs overseas”.