It is commonly accepted that the dingo arrived in Australia approximately 4,000 years ago, and that the current population of dingoes across Australia grew from just one pregnant female. However, this was just an hypothesis posited by geneticist Dr Alan Wilton (deceased), and was never meant to be taken as fact. In the last paper he wrote before he died, Dr Wilton suggested that dingoes were more likely to have been introduced some 11,000 – 18,000 years ago [1]. In a recent genetics study, Dr Wilton’s partner, Dr Kylie Cairns found that there were most likely two introductions of dingoes to Australia, not just one .[2] One introduction was to the North-west of the country, and the other was to the South-east.

It is commonly accepted that the dingo arrived in Australia approximately 4,000 years ago, and that the current population of dingoes across Australia grew from just one pregnant female. However, this was just an hypothesis posited by geneticist Dr Alan Wilton (deceased), and was never meant to be taken as fact. In the last paper he wrote before he died, Dr Wilton suggested that dingoes were more likely to have been introduced some 11,000 – 18,000 years ago [1]. In a recent genetics study, Dr Wilton’s partner, Dr Kylie Cairns found that there were most likely two introductions of dingoes to Australia, not just one .[2] One introduction was to the North-west of the country, and the other was to the South-east.

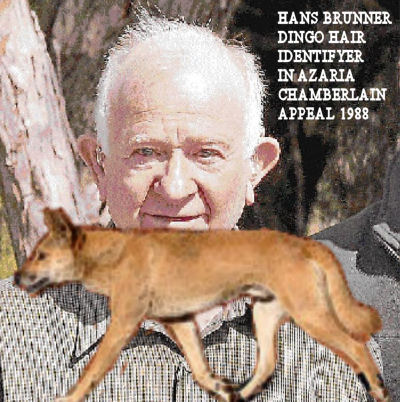

Candobetter.net editor: The remarkable photographs of dingos in this document were taken by the author, Jennifer Parkhurst. As well as being a naturalist with years of dingo-dedicated fieldwork behind her, Jennifer Parkhurst is a great photographer. She is the author of two illustrated books about Dingos, Vanishing Icon and the most recent, The Butchulla First Nations People of Fraser Island (K’Gari) and their dingoes.

The remarkable photographs of dingos in this document were taken by the author, Jennifer Parkhurst. As well as being a naturalist with years of dingo-dedicated fieldwork behind her, Jennifer Parkhurst is a great photographer. She is the author of two illustrated books about Dingos, Vanishing Icon and the most recent, The Butchulla First Nations People of Fraser Island (K’Gari) and their dingoes.

It is also commonly thought that dingoes were brought to Australia by Asian seafarers, but another hypothesis is that dingoes spread into what is now Australia via the land bridge between Papua New Guinea and Australia, some 8,000 years ago. Dingoes were declared indigenous to Australia in 1992 and are protected under legislation. However, they are also classified as a pest animal due to their predation on livestock, and with varying legislation in each state, the complexities of protecting them as a native taxon can be very frustrating.

Current taxonomy classifies the dingo as a subspecies of Canis lupus (wolf) that is, Canis lupus dingo . However, the classification Canis dingo was proposed in a 2014 study that established a reference description of the dingo based on pre-20th century specimens that are unlikely to have been influenced by hybridisation. [3] Dingoes are now, therefore, increasingly considered a species in their own right. However, current methods of identifying dingoes are inadequate because natural variation within dingo populations is poorly understood. Skull morphology and DNA testing techniques are not reliable. Geneticist, Dr Alan Wilton, who developed the current dingo purity test, stipulated that dingoes which test between 75 and 100 per cent pure should be treated as ‘pure’ for the purposes of conservation in the wild. In addition, there is considerable differentiation in the colour of dingoes including numerous combinations of white, ginger, black, and black and tan. Most people expect dingoes to be ginger and deem anything of a different colour to be hybrid.

Hybridisation of dingoes is said to be the biggest threat to their survival. However there is little evidence that moderately hibridised dingoes are dangerous to the environment. In fact, the opposite seems to be the case. Most all modern dingoes will have some genetic dog markers, but they behave and act like dingoes. Dingoes howl instead of barking, reproduce only once a year, and live in stable packs. It is only when these packs are fractured due to lethal control that hybridisation becomes more likely. A stable pack contains an alpha male and female, and offspring from the previous year plus pups. The alpha male and female suppress breeding by subordinate pack members, naturally keeping the population in balance. Dingoes can suppress breeding altogether in times of drought, fire, or when food is low for any other reason. A domestic dog would have a great deal of trouble infiltrating a stable dingo pack. However, if, due to lethal control, the pack is fractured, then the subordinate members would be more likely to mate with domestic dogs, thus creating a situation where there are more dingoes, not less. With no stable pack to teach the new parents and pups how to behave and what to hunt, they become like unruly teenagers and run amok, hunting anything and everything indiscriminately. Subsequently, the use of lethal control causes more problems than it solves.

Dingoes are territorial and are formidable in protecting their territories from intruders. Dingoes will only take farm stock if there is a shortage of natural food, and studies have shown that despite the fact that dingoes are regarded as predators of sheep and cattle, domestic livestock do not comprise a significant part of foods eaten. [4]

Stable dingo packs, therefore, offer a level of protection to farms from intruders such as free-ranging domestic dogs which are known to attack stock at will, not with the intention of eating what they kill, but killing without purpose. When a pack is fractured, these domestic dogs, which form into packs at night, predate on stock animals. Pastoralists who do not use lethal control on their properties find that they have less stock predation than those who do. [5]

Even so, there is little chance that severely hybridised offspring would survive in the wild. Without the characteristics of the dingo which are tailored to Australia’s harsh environment, hybrids would die out quickly. If they manage to survive and reproduce, eventually, after several generations, the genetics revert back to the ancestral dingo form.

Herein lies a conservation dilemma: some dingo conservationists want to preserve only pure dingoes, while others want to conserve dingo hybrids as well. There is a growing body of evidence which suggests that protecting dingo hybrids is beneficial for the environment as long as they are performing their role as top-order predator, protecting our native animals from introduced species like feral cats, foxes, pigs, goats and deer. They also keep native animals such as kangaroos at bay, which left unchecked, can cause just as many if not more problems for farmers as the dingoes themselves, by eating pasture grass and drinking stock water.

Dingoes are protected in national parks; however the same national parks are baited with sodium monofluoroacetate(1080 poison) to control foxes, paradoxically making national parks extremely hostile places for our top-order predator to live. This bait is indiscriminate and cruel, and not only kills foxes, but of course, dingoes, as well as other non-target animals like the endangered quoll, birds of prey, goannas and any carrion-eating animal. 1080 is said to be harmless to the environment because it is derived from native plants, but the bait is a synthetic substance which our native animals have no tolerance for. There is no antidote. 1080 can stay active in the environment, polluting waterways and flora, for 12 months or more. Again, baiting has the capacity to destroy dingo pack structure and cause social dysfunction within dingo populations, in turn undermining their ecosystem function. Despite unrelenting baiting, farmers are finding that they still have problems with dingoes. Efforts to eradicate dingoes are not working. Predator-friendly farming should be the way of the future.

Australia is the only country where its top-order predator is not safe anywhere.

Some states of Australia have a ‘wild dog’ bounty system in place, paying up to $120 per dingo scalp. Bounties have been found to be ineffective at reducing dingo numbers (or foxes or whatever else is targeted).

In a recent media release (17 Nov 2016) The Wilderness Society stated:

Previously, dingoes and wild dogs were targeted strategically, in areas where farmers were experiencing stock loss problems.

In contrast, the bounty system applies to very large areas – over half of the relevant public land in eastern Victoria is subject to the bounty – regardless of whether livestock protection is required.

The key issues are poorly informed members of the public unnecessarily killing dingoes and dingo hybrids, and the subsequent disruption of pack structures - believed to result in changes to territorial boundaries, and the increased risk of hybridisation and stock loss.

Lost in all of this is the importance the dingo holds for the Aboriginal First Nations People. Irrespective of when and how the dingo came to Australia, it was immediately adopted by the Aboriginal people and took on an important role in their lives. It is speculated that dingoes helped with hunting, but this sometimes questioned. We do know that the Aboriginal people were very fond of their dingoes; women nursed them from their own breasts as puppies, or expressed milk for them; when the adults went hunting, dingoes were left behind at camp to look after the children, keeping them safe from both evil spirits, and more corporeal dangers, like snakes and other intruders. Dingoes were often carried on walkabout, and were objects of great affection. In some tribes, dingoes were a totem animal; sacred. If a dingo was harmed in any way, punishment was often death. When a person died, often times his dingo companion was buried with him. [6]

The Aboriginal people have practically no voice in the ‘dingo: friend or foe’ debate, except perhaps on Fraser Island where they have stated that the white people first tried to eradicate them, and now they are trying to eradicate their dog.

‘They had us leave this Country, removed us, and it looks like they want to remove the dingoes. It is history repeating itself, only [now] it is the dingoes, which is part of our life. When the dingo is endangered, we feel like part of our culture is endangered.’ [7]

The dingo has always been an ancient semi-domesticate animal, living symbiotically with the Aboriginal people and up until recently, in places on Fraser Island, with white Australians. For the most part today the dingo is elusive, but historically dingoes often befriended wandering swaggies or cattlemen on their journeys across the country or around their properties.

So how do we save the dingoes? The National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program Inc (NDPRP) is currently focusing its energies on two places: Victoria, in the hope we can set precedents there, which we can then lobby other states with; and Fraser Island in Queensland because of the impending extinction of the iconic Fraser Island dingo which has its own unique characteristics.

The members of the NDPRP were instrumental in having the dingo listed as a threatened species in Victoria, under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act. Although protections are in place for ‘pure’ dingoes under this Act, those protections are currently being undermined by the influence of two fishers and hunters members in the Victorian Legislative Council, who exercise disproportionate influence over the Victorian government. It is this influence which explains the recent reintroduction of a ‘wild dog’ bounty in Victoria despite Victoria having been the first state to list the dingo as threatened.

Over the past two decades or so, a body of research evidence has grown, which shows that stable, healthy dingo populations have a net beneficial effect upon ecosystem stability. This research coincided with a growing international focus on the importance of apex predators for ecosystem maintenance and presented a direct challenge to entrenched anti-dingo prejudice in Australia. More recently, there has been a concerted counter-reaction from extreme elements within the pastoral lobby in an attempt to discredit earlier apex predator research findings and to reassert anti-dingo dogma.

In collaboration with the Humane Society International, the Wilderness Society, the Australian Wildlife Protection Council, Save Fraser Island Dingoes, Eagle’s Nest Wildlife Sanctuary, scientists, and other groups, we are constantly lobbying for legislative change on a number of issues, the main two being 1/ to broaden the definition of the dingo, and 2/ to cease lethal control, or limit areas where it is deployed.

Other measures to protect livestock have been shown to be very effective, including the use of Maremma guard dogs. Financial compensation for stock loss might also be tried. The cost of lethal control would far outweigh the cost of reimbursing farmers for stock loss.

The most effective form of dingo control however, would be to leave dingoes alone, stop lethal control altogether, and let the ecosystem recover.

18 November 2016

Jennifer Parkhurst

Vice President – National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program Inc (A0051763G )

Consultant – Save Fraser Island Dingoes

Email the author http://www.fraserislandfootprints.com/

[1]Mattias C. R. Oskarsson1, Cornelya F. C. Klu¨ tsch, Ukadej Boonyaprakob, Alan Wilton, Yuichi Tanabe and Peter Savolainen. 2011. Mitochondrial DNA data indicate an introduction through Mainland Southeast Asia for Australian dingoes and Polynesian domestic dogs. Proc. R. Soc. B doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.1395

[2] Cairns, Kylie M. Wilton, Alan N. New insights on the history of canids in Oceania based on mitochondrial and nuclear data

Genetica DOI 10.1007/s10709-016-9924-z

[3] Crowther, M. S.; M. Fillios; N. Colman; M. Letnic (27 Mar 2014). "An updated description of the Australian dingo (Canis dingo Meyer, 1793)". Journal of Zoology. 293 (3): 192. doi:10.1111/jzo.12134.

[4] SJO Whitehouse. 1977. The Diet of the Dingo in Western Australia. Aust Wildlife Res, 1977, 4, 145-50

[5] ABC Rural. 2013.Lee Allen: Surprise finding: dog baiting increases stock loss.

[6] Australian Dingo Conservation Foundation. http://www.dingoconservation.org.au/aboriginal.html

[7]Jennifer Parkhurst. 2015. The Butchulla First Nations People of Fraser Island (K’Gari) and their dingoes. Australian Wildlife Protection Council, Ross House, Melbourne Victoria.

Wildlife advocacy initiative Defend the Wild has called on the Andrews Government to halt the killing of Victoria’s threatened dingoes after harrowing footage of dingoes being trapped and shot obtained by the group was revealed on the ABC’s 7.30 Report last night.

Wildlife advocacy initiative Defend the Wild has called on the Andrews Government to halt the killing of Victoria’s threatened dingoes after harrowing footage of dingoes being trapped and shot obtained by the group was revealed on the ABC’s 7.30 Report last night.

Dr John Kingston, Veterinary Advisor to Australia's National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program, says that the internationally beloved dingoes of Fraser Island (K'Gari) have all but disappeared from their beach territories as government authorities condemn survivors to a cruel death by starvation.

Dr John Kingston, Veterinary Advisor to Australia's National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program, says that the internationally beloved dingoes of Fraser Island (K'Gari) have all but disappeared from their beach territories as government authorities condemn survivors to a cruel death by starvation.

‘Stop the Drop’: Ban Aerial Baiting with 1080 Poison, Treasury Gardens Melbourne (Lawn 4), November 24, 5 -8 pm. Since 2014, Victorian governments have been routinely dropping tonnes of cruel 1080 poison over vast areas of the Victorian natural environment from helicopters. Supposedly to protect farm stock from ‘wild dogs’, it is of virtually no benefit to farmers and nothing to do with ‘wild dogs’. The ‘wild dogs’ being killed are really Dingoes, the native Australian apex predator, a threatened species in Victoria and essential to the stability and health of Victorian ecosystems.

‘Stop the Drop’: Ban Aerial Baiting with 1080 Poison, Treasury Gardens Melbourne (Lawn 4), November 24, 5 -8 pm. Since 2014, Victorian governments have been routinely dropping tonnes of cruel 1080 poison over vast areas of the Victorian natural environment from helicopters. Supposedly to protect farm stock from ‘wild dogs’, it is of virtually no benefit to farmers and nothing to do with ‘wild dogs’. The ‘wild dogs’ being killed are really Dingoes, the native Australian apex predator, a threatened species in Victoria and essential to the stability and health of Victorian ecosystems.  While expressing sympathy for the child injured by a dingo on Fraser Island around midnight on April 18, and for the child’s parents, the

While expressing sympathy for the child injured by a dingo on Fraser Island around midnight on April 18, and for the child’s parents, the  Dingoes play a key role in the conservation of Australian outback ecosystems by suppressing feral cat populations, a UNSW Sydney study has found. A UNSW Sydney study has ended an argument about whether or not dingoes have an effect on feral cat populations in the outback, finding that the wild dogs do indeed keep the wild cat numbers down.

Dingoes play a key role in the conservation of Australian outback ecosystems by suppressing feral cat populations, a UNSW Sydney study has found. A UNSW Sydney study has ended an argument about whether or not dingoes have an effect on feral cat populations in the outback, finding that the wild dogs do indeed keep the wild cat numbers down.

A UNSW Sydney study says more evidence is needed before declaring the dingo a feral animal, casting a shadow over state governments’ justification for culling Australia’s largest carnivorous mammal. There is no conclusive evidence that the Australian dingo was once domesticated, UNSW scientists reveal, challenging the notion that the animal is therefore feral.

A UNSW Sydney study says more evidence is needed before declaring the dingo a feral animal, casting a shadow over state governments’ justification for culling Australia’s largest carnivorous mammal. There is no conclusive evidence that the Australian dingo was once domesticated, UNSW scientists reveal, challenging the notion that the animal is therefore feral.

The National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program (NDPRP) today expressed dismay at the failure of the Victorian Labor government to put its own apex predator conservation policy into practice.

The National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program (NDPRP) today expressed dismay at the failure of the Victorian Labor government to put its own apex predator conservation policy into practice.  In response to claims that DNA from a 350-year-old dingo tooth could save the species in Australia, National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program spokesperson Dr Ian Gunn said the reverse was the case. “On past experience, the evidence will be used to justify a continued sheep industry campaign to exterminate the species across Australia. Just because of the introgression of domestic dog genetics in some individuals, or because they are not the dingo variety identified by the genes in this ‘one-tooth’, they then falsely claim the animals they are killing are not real dingoes."

In response to claims that DNA from a 350-year-old dingo tooth could save the species in Australia, National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program spokesperson Dr Ian Gunn said the reverse was the case. “On past experience, the evidence will be used to justify a continued sheep industry campaign to exterminate the species across Australia. Just because of the introgression of domestic dog genetics in some individuals, or because they are not the dingo variety identified by the genes in this ‘one-tooth’, they then falsely claim the animals they are killing are not real dingoes."  The Andrews Labor government has just failed a crucial test of its integrity in relation to threatened species listings and biodiversity governance. Immediately prior to losing office in December 2010, the Brumby Labor government had finalized listing the dingo as a threatened native taxon under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act.

The Andrews Labor government has just failed a crucial test of its integrity in relation to threatened species listings and biodiversity governance. Immediately prior to losing office in December 2010, the Brumby Labor government had finalized listing the dingo as a threatened native taxon under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act.  It is commonly accepted that the dingo arrived in Australia approximately 4,000 years ago, and that the current population of dingoes across Australia grew from just one pregnant female. However, this was just an hypothesis posited by geneticist Dr Alan Wilton (deceased), and was never meant to be taken as fact. In the last paper he wrote before he died, Dr Wilton suggested that dingoes were more likely to have been introduced some 11,000 – 18,000 years ago [1]. In a recent genetics study, Dr Wilton’s partner, Dr Kylie Cairns found that there were most likely two introductions of dingoes to Australia, not just one .[2] One introduction was to the North-west of the country, and the other was to the South-east.

It is commonly accepted that the dingo arrived in Australia approximately 4,000 years ago, and that the current population of dingoes across Australia grew from just one pregnant female. However, this was just an hypothesis posited by geneticist Dr Alan Wilton (deceased), and was never meant to be taken as fact. In the last paper he wrote before he died, Dr Wilton suggested that dingoes were more likely to have been introduced some 11,000 – 18,000 years ago [1]. In a recent genetics study, Dr Wilton’s partner, Dr Kylie Cairns found that there were most likely two introductions of dingoes to Australia, not just one .[2] One introduction was to the North-west of the country, and the other was to the South-east.

The remarkable photographs of dingos in this document were taken by the author, Jennifer Parkhurst. As well as being a naturalist with years of dingo-dedicated fieldwork behind her, Jennifer Parkhurst is a great photographer. She is the author of two illustrated books about Dingos, Vanishing Icon and the most recent,

The remarkable photographs of dingos in this document were taken by the author, Jennifer Parkhurst. As well as being a naturalist with years of dingo-dedicated fieldwork behind her, Jennifer Parkhurst is a great photographer. She is the author of two illustrated books about Dingos, Vanishing Icon and the most recent,

This document was forwarded to candobetter.net by the National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program Inc. (A0051763G). On October 17, the Victorian Wilderness Society, in its Wild Chat bulletin wrote: "Hunting Dingoes, Logging Koalas, Pounding Plovers, and Heeding Dr Seuss Bounty brings uncontrolled threat to Victoria’s dingoes." The bulletin concluded, "It now appears the Andrews Government has lost its way, and is taking a regressive step towards failure for both dingo conservation and a balanced resolution of conservation and farming interests." We republish here the contents of that bulletin.

This document was forwarded to candobetter.net by the National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program Inc. (A0051763G). On October 17, the Victorian Wilderness Society, in its Wild Chat bulletin wrote: "Hunting Dingoes, Logging Koalas, Pounding Plovers, and Heeding Dr Seuss Bounty brings uncontrolled threat to Victoria’s dingoes." The bulletin concluded, "It now appears the Andrews Government has lost its way, and is taking a regressive step towards failure for both dingo conservation and a balanced resolution of conservation and farming interests." We republish here the contents of that bulletin. There has been a lot of discussion about the benefits likely from the return of traditional animal predators into the Australian environment. In Victoria Toolern Vale’s Australian Dingo Foundation, Aus Eco Solutions and Mt Rothwell Biodiversity Interpretation Centre in Little River have launched the Working Dingoes Saving Wildlife project. Inside is a link to the ABC film reporting this. And we have also embedded another film about the impact of returning wolves to Yellowstone Park in the United States, whence they had been absent for about 70 or more years. The effects were positive and remarkable. This is a short and enjoyable film, narrated by George Monbiot.

There has been a lot of discussion about the benefits likely from the return of traditional animal predators into the Australian environment. In Victoria Toolern Vale’s Australian Dingo Foundation, Aus Eco Solutions and Mt Rothwell Biodiversity Interpretation Centre in Little River have launched the Working Dingoes Saving Wildlife project. Inside is a link to the ABC film reporting this. And we have also embedded another film about the impact of returning wolves to Yellowstone Park in the United States, whence they had been absent for about 70 or more years. The effects were positive and remarkable. This is a short and enjoyable film, narrated by George Monbiot. Compassion was a far more effective environmental management tool than “poison and guns,” award winning ecologist Dr Arian Wallach told a recent conference of conservationists and farmers. And dingoes were an ideal agent for saving the environment and promoting co-existence between native and exotic species. The May 17, 2015 conference, “Dingo – Friend or Foe” was held at Hervey Bay Community Centre, just across the Great Sandy Straits from World Heritage listed Fraser Island where, it was argued, Australia’s war on the dingo began. Three prominent local farmers, Harry Jamieson, Lindsay Titmarsh and James Hansen told the conference of dingo problems, worse in recent years than ever before. (Article by Arthur Gorrie. )

Compassion was a far more effective environmental management tool than “poison and guns,” award winning ecologist Dr Arian Wallach told a recent conference of conservationists and farmers. And dingoes were an ideal agent for saving the environment and promoting co-existence between native and exotic species. The May 17, 2015 conference, “Dingo – Friend or Foe” was held at Hervey Bay Community Centre, just across the Great Sandy Straits from World Heritage listed Fraser Island where, it was argued, Australia’s war on the dingo began. Three prominent local farmers, Harry Jamieson, Lindsay Titmarsh and James Hansen told the conference of dingo problems, worse in recent years than ever before. (Article by Arthur Gorrie. ) Researcher and grazier Adam O’Neill said the national “war on the dingo” which followed the death of a boy, Clinton Gage on Fraser Island in 2001 had caused a significant worsening of the problems it was supposed to address.

Researcher and grazier Adam O’Neill said the national “war on the dingo” which followed the death of a boy, Clinton Gage on Fraser Island in 2001 had caused a significant worsening of the problems it was supposed to address. I was inspired to write this short article after reading evolutionary sociologist Sheila Newman's multi-species population work on cooperative breeding and incest avoidance in Demography, Territory, Law: The Rules of Animal and Human Population, Countershock Press, 2013, chapters 3 and 4. Newman gives theory plus examples of self-controlled populations in variety of species. My primary observation of dingo breeding habits in their native habitat supports this theory and is supported by it.

I was inspired to write this short article after reading evolutionary sociologist Sheila Newman's multi-species population work on cooperative breeding and incest avoidance in Demography, Territory, Law: The Rules of Animal and Human Population, Countershock Press, 2013, chapters 3 and 4. Newman gives theory plus examples of self-controlled populations in variety of species. My primary observation of dingo breeding habits in their native habitat supports this theory and is supported by it. Dingoes have the ability to self-regulate their population, and avoid breeding when times are lean, by suppressing their own estrus (female) and testrus (male) cycles. In normal circumstances, the alpha male and female are able to suppress breeding in subordinate pack (family) members, so that only one pair out of each pack reproduces. A stable dingo pack includes the alpha male and female, and surviving pups from the previous year’s litter. These pups have a vital role as beta pack members, who perform the task of ‘alloparental helper’, to wet-nurse, regurgitate food and deliver food (carcasses) for the pups and to provision the mother.

Dingoes have the ability to self-regulate their population, and avoid breeding when times are lean, by suppressing their own estrus (female) and testrus (male) cycles. In normal circumstances, the alpha male and female are able to suppress breeding in subordinate pack (family) members, so that only one pair out of each pack reproduces. A stable dingo pack includes the alpha male and female, and surviving pups from the previous year’s litter. These pups have a vital role as beta pack members, who perform the task of ‘alloparental helper’, to wet-nurse, regurgitate food and deliver food (carcasses) for the pups and to provision the mother.  With the destruction of yet another juvenile dingo on Fraser Island, the Australian Wildlife Protection Council (AWPC) and the National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program (NDPRP) today issued a joint criticism of the Queensland Government for its continuing mismanagement of the Fraser Island dingo population.

With the destruction of yet another juvenile dingo on Fraser Island, the Australian Wildlife Protection Council (AWPC) and the National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program (NDPRP) today issued a joint criticism of the Queensland Government for its continuing mismanagement of the Fraser Island dingo population.

This is an article based on a complaint from the National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program to the Australian Press Council about an Opinion article, “Marauding wild dog packs wreak havoc in outback Queensland pushing drought-plagued graziers to the wall” (Courier Mail (Queensland), December 06, 2014. Statements in the article are made which, by omission of key facts, and encouragement of prejudice, misrepresent the reasons for the decline in the sheep industry in Queensland. This misrepresentation by omission is used to manufacture an exaggerated account of the role of the dingo in the demise of the sheep grazing industry in that state.

This is an article based on a complaint from the National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program to the Australian Press Council about an Opinion article, “Marauding wild dog packs wreak havoc in outback Queensland pushing drought-plagued graziers to the wall” (Courier Mail (Queensland), December 06, 2014. Statements in the article are made which, by omission of key facts, and encouragement of prejudice, misrepresent the reasons for the decline in the sheep industry in Queensland. This misrepresentation by omission is used to manufacture an exaggerated account of the role of the dingo in the demise of the sheep grazing industry in that state. Such misleading statements include:

Such misleading statements include:

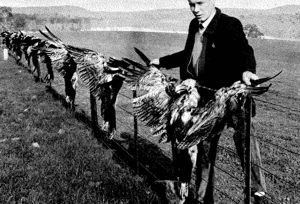

The cruel changes made by the Napthine Victorian Government to wildlife laws are another reason many might not have known to be glad that its term just ended. It reestablished wild dog control zones across eastern Victoria which go well beyond the three kilometre limit into public land established under Labor. It reintroduced trap types previously banned by Labor as cruel. It introduced a bounty system whereby recreational hunters (including those using bows and arrows) can kill dingoes (‘wild dogs’) for profit across large parts of eastern Victoria and in the Big Desert National Park in western Victoria. Bounties can be taken in the Big Desert region even though there are no wild dog control zones in that part of the state. It increased the period allowed by Labor between trap visitations to 72 hours. Labor had previously reduced the trap visitation time to limit cruelty. it introduced aerial baiting in Victoria, which had not been permitted by the Brumby Labor government. And that's not all.

The cruel changes made by the Napthine Victorian Government to wildlife laws are another reason many might not have known to be glad that its term just ended. It reestablished wild dog control zones across eastern Victoria which go well beyond the three kilometre limit into public land established under Labor. It reintroduced trap types previously banned by Labor as cruel. It introduced a bounty system whereby recreational hunters (including those using bows and arrows) can kill dingoes (‘wild dogs’) for profit across large parts of eastern Victoria and in the Big Desert National Park in western Victoria. Bounties can be taken in the Big Desert region even though there are no wild dog control zones in that part of the state. It increased the period allowed by Labor between trap visitations to 72 hours. Labor had previously reduced the trap visitation time to limit cruelty. it introduced aerial baiting in Victoria, which had not been permitted by the Brumby Labor government. And that's not all. (Illustration cropped from a photograph by Clive A Marks in an Age article entitled "In wild dog country, all death is merciless," by Melissa Fyfe at

(Illustration cropped from a photograph by Clive A Marks in an Age article entitled "In wild dog country, all death is merciless," by Melissa Fyfe at President of the National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program

President of the National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program A spokesperson for the National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program (NDPRP) today,Thursday, August 21st, 2014, expressed concern and disappointment that the Gympie Regional Council appears to have exercised no independence of thought in adopting a ‘Wild Dog’ control plan, which is ill-informed and based largely on prejudice.

A spokesperson for the National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program (NDPRP) today,Thursday, August 21st, 2014, expressed concern and disappointment that the Gympie Regional Council appears to have exercised no independence of thought in adopting a ‘Wild Dog’ control plan, which is ill-informed and based largely on prejudice. NDPRP Secretary, Dr Ernest Healy, stated that the NDPRP is disappointed that the Gympie Regional Council has adopted a ‘wild dog’ control plan with justifications that are either now shown by scientific research to be false or based on a selective, unbalanced consideration of the available scientific evidence. He said that, "In doing so, the Council is perpetuating a misguided and alarmist perspective on ‘wild dogs’, or dingoes, which ignores their importance for health of ecosystems."

NDPRP Secretary, Dr Ernest Healy, stated that the NDPRP is disappointed that the Gympie Regional Council has adopted a ‘wild dog’ control plan with justifications that are either now shown by scientific research to be false or based on a selective, unbalanced consideration of the available scientific evidence. He said that, "In doing so, the Council is perpetuating a misguided and alarmist perspective on ‘wild dogs’, or dingoes, which ignores their importance for health of ecosystems." President of the National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program, and animal research ethics expert, Dr Ian Gunn, stated today, Wednesday 20 August, 2014, that the recent destruction of three sub-adult dingoes on Fraser Island for an alleged ‘savage’ attack is a poor reflection upon the new Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service dingo management strategy.

President of the National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program, and animal research ethics expert, Dr Ian Gunn, stated today, Wednesday 20 August, 2014, that the recent destruction of three sub-adult dingoes on Fraser Island for an alleged ‘savage’ attack is a poor reflection upon the new Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service dingo management strategy. Independence of Queensland Liberal National Party Government Fraser Is. Dingo management policy review has been questioned by the SFID. Why is previous management involved in review of its own record? SFID believes there are a number of high-profile and more suitable ecologists in Australia with experience more directly relevant to dingo conservation who could and should have been recruited to the policy review. The history of dingo management on Fraser Island has been disgraceful.

Independence of Queensland Liberal National Party Government Fraser Is. Dingo management policy review has been questioned by the SFID. Why is previous management involved in review of its own record? SFID believes there are a number of high-profile and more suitable ecologists in Australia with experience more directly relevant to dingo conservation who could and should have been recruited to the policy review. The history of dingo management on Fraser Island has been disgraceful.

Dingoes on Fraser Island, Australia are dying of starvation, with sand and grass in their stomachs. One woman tried to alert the world to this and was sentenced and fined for her trouble. On 25th of August 2012 Jennifer Parkhusrt received a national award from the

Dingoes on Fraser Island, Australia are dying of starvation, with sand and grass in their stomachs. One woman tried to alert the world to this and was sentenced and fined for her trouble. On 25th of August 2012 Jennifer Parkhusrt received a national award from the

Human exposure to 1080 is very severely restricted by law, for obvious reasons. The same does not apply to other species in baited areas. The major animal welfare concern over the use of 1080 relates to its extreme cruelty and its lack of an antidote. The major environmental concern relates to its effects on non target animals, either through ingestion of baits or by secondary poisoning.

Human exposure to 1080 is very severely restricted by law, for obvious reasons. The same does not apply to other species in baited areas. The major animal welfare concern over the use of 1080 relates to its extreme cruelty and its lack of an antidote. The major environmental concern relates to its effects on non target animals, either through ingestion of baits or by secondary poisoning.  (Photo of Eastern Grey joey, "Acacia," by Brett Clifton.The late Dr Peter Rawlinson La Trobe University zoologist stated in 1987 (as an Australian Conservation Foundation Councillor):

(Photo of Eastern Grey joey, "Acacia," by Brett Clifton.The late Dr Peter Rawlinson La Trobe University zoologist stated in 1987 (as an Australian Conservation Foundation Councillor):  "The land treated could easily have been treated for possum control by safer alternative methods, ie. trapping and ferratox in bait stations, as it is NOT REMOTE, NOT INNACCESSIBLE, and NOT RUGGED TERRAIN.

"The land treated could easily have been treated for possum control by safer alternative methods, ie. trapping and ferratox in bait stations, as it is NOT REMOTE, NOT INNACCESSIBLE, and NOT RUGGED TERRAIN. Media Release... Exactly as I or anyone would have thought. A hungry dog is more likely to approach people and try and get food, and then they have to be "managed" to prevent attacks. It's all a self-fulfilling prophesy to keep their numbers down for tourism. The fine was more about upsetting the status quo and about having their little scheme exposed for what it is. People living on islands don't usually survive without importing food. Why should these animals have to? "Sustainable" numbers for dingoes is one thing, but "sustainable" human numbers - and their overshoot - gets ignored.

Media Release... Exactly as I or anyone would have thought. A hungry dog is more likely to approach people and try and get food, and then they have to be "managed" to prevent attacks. It's all a self-fulfilling prophesy to keep their numbers down for tourism. The fine was more about upsetting the status quo and about having their little scheme exposed for what it is. People living on islands don't usually survive without importing food. Why should these animals have to? "Sustainable" numbers for dingoes is one thing, but "sustainable" human numbers - and their overshoot - gets ignored. In terms of environmental management Australia is just a collection of colonies not unlike the days of very early settlement. Policies that govern the control of feral animals and natives that are perceived as pests differ from state to state (and territory).

In terms of environmental management Australia is just a collection of colonies not unlike the days of very early settlement. Policies that govern the control of feral animals and natives that are perceived as pests differ from state to state (and territory).

Recent comments