Preview

Joseph Wayne Smith

Discipline of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

School of Paediatrics and Reproductive Health

University of Adelaide

This book by evolutionary sociologist Sheila Newman, is book one of four books developing an evolutionary and ecological sociological study of the biological basis of politics, economy and demography. It is a broad-ranging multidisciplinary approach to the study of human society which sociology has long ago abandoned for a descent into jargon, word games and empirically unsubstantiated theory. Not so for Newman who believes and demonstrates that sociology can be scientific, but only if it abandons its isolationist Durkheimian commitment to seeing social facts as sui generis.

The subtitles of the other forthcoming volumes in Newman’s master work are: Volume 2: Land Tenure and the Origins of Capitalism in Britain; Volume 3: Land Tenure and the Origins of Modern Democracy in France; Volume 4: After Napoleon: Incorporation of Land and People. The collected works promises to be, judged by the outstanding merits of the present volume under review, one of the most important contributions to sociology in recent times. Newman systematically applies insights from a wide range of sciences. Further, and refreshingly, she is a French speaker as well as other Latin-based languages, and she has studied the history and philology of Roman language, all giving her access to debates outside of the Anglosphere.

The principal thesis of The Rules of Animal and Human Populations is that both human and animal societies have distinct patterns of dispersal. These patterns affect the size of populations, and in humans, the very nature of economic and political systems. Thus, different land-use, planning and inheritance systems have different outcomes, with some systems resulting in sustainable steady-state economies, while others are geared to exponential growth, the ultimate price of which is collapse. Peeping ahead, clan-based communities, in the Pacific and New Guinea for example, where traditional land-use and inheritance systems are retained, people retain control over natural resources and do not commodify the land by buying and selling it. People strive to prevent, as best they can, natural resources from being alienated and destroyed. This contrasts with the fossil-fuel intensive Anglophone countries where almost everything which can be commodified, has been. These countries are facing a multi-dimensional environmental crisis that is likely to result in social breakdown and dislocation. When collapse does occur societies’ property ownership returns to family connections with the land, and over time the family and clan system re-emerges. Newman hopes that people in the rapidly growing Anglophone societies may be able to regain these organic systems of social organisation as protection against the onslaught of global capitalism.

Newman argues that these seemingly unstoppable forces of population and economic growth which are leading Anglophone countries like the United States, Australia, Britain and Canada to overshoot, do not exist in the Western continental European systems. Europe’s population is already too big and is causing environmental destruction, but natural attrition is downsizing the population to more sustainable levels. Writers like “Spengler”, David P. Goldman, in books with melodramatic titles such as It’s Not the End of the World, It’s Just the End of You, (RVP, New York, 2011), raise an alarm about such a decrease in population, but ecologically it is really just the population returning to more sustainable levels. By contrast, countries such as Australia, through undemocratically imposed immigration, largely produced by the lobbying muscle of powerful ethnic and business groups (especially the housing/real estate lobby), are set to push their populations to completely unsustainable levels, paying no respect to environmental and resources crises such as peak oil. Part of the problem with Australia’s runaway growth in population, Newman points out, is that people, as in other Anglophone countries, have little democratic power to defend communities from the assault of the forces of the market, by contrast to continental Europe where the state controls most of the land-use.

Anglophone countries have political and business elites dogmatically committed to unending economic growth and “progress.” Progress has become a secular religion for them. In chapter 1 Newman subjects this religion of progress to a penetrating critique. Progress requires vast quantities of materials and energy, in the form of fossil fuels. What happens in complex computer societies if there is no longer abundant fossil fuel? Is freedom, democracy and “progress” in such complex societies a product of relatively cheap fossil fuel, and will these institutions disappear in the coming age of scarcity? Her answer is “yes”, for democracy in the sense of full participation in decisions is more likely in small communities not based on techno-industrialism. She sees “peak oil” and the rapid depletion of other resources needed for techno-industrial societies to grow, as major forces terminating their lives.

If economists have been wrong about the ideology of progress, what else have they been wrong about? Chapter 2 of Rules of Animal and Human Populations discusses myths of fertility and mortality that have dominated contemporary anthropology, especially the idea that hunter-gatherer societies, supposedly lacking mechanical contraception, only maintain stable populations through Malthusian forces and violence, producing high mortality. Newman goes to considerable lengths in this chapter to show that modern anthropology has forgotten a massive body of evidence about “pre-transitional” societies, such as the Kunimaipa people in the highlands of Papua New guinea, who maintain stable populations through a variety of strategies such as breastfeeding for four or five years, abortion, infanticide and post-partum taboos. Other societies have used equally as innovative strategies to prevent women being sexually active during a large part of their adult life, including norms of premarital virginity, incest avoidance and other restrictions. For example, brothers traditionally shared one wife in Tibet leaving 30 percent of women without an opportunity for marriage. Surprisingly enough, even Malthus documented cases of stable populations in continental Europe at the end of the 18th century, such as the Swiss parish of Leyzin. There are, though, other important factors including incest avoidance and the Westermarck effect which Newman discusses in depth.

Newman advances a new theory about how incest avoidance and the Westermarck effect impact upon patterns of human settlement and population growth. Incest avoidance, the avoidance of inbreeding, is not limited to humans but occurs in many other organisms including cockroaches. Second, the Westermarck effect, first observed by 19th century Finnish sociologist Edvard Westermarck (1862-1939), is that incest avoidance also applies to people raised together independent of whether or not they are genetically related. The effect has been confirmed many times. Newman argues that contrary to received sociology, incest avoidance and the Westermarck effect are probably indistinctive norms in humans, a product of genetic algorithms underpinning human social organisation. Inbreeding avoidance occurs in many other species, including plants, suggesting that a mechanism such as hormones may be the generative mechanism rather than conscious calculations. In short; “hormones will deliver more or less fertility according to the availability of living space. Space (territory) required per individual will be affected by density and reliability of food distribution, and all of this will be mediated by some degree of incest avoidance/Westermarck effect, which is also related to social dominance.” (p.83)

Incest avoidance and the Westermarck effect have the impact of avoiding the genetic ills of inbreeding, producing fewer homozygous defective genes, but beyond this, incest avoidance regulates population size and density so that animals would have more territory than if numbers were greater without restrictions on inbreeding. For humans, Newman argues, population dispersal and spatial organisation are a function of incest avoidance. Conventional sociology holds that incest avoidance is achieved by modes of population dispersal, but Newman proposes that incest avoidance itself causes dispersal. The same algorithms of population spacing found in other species are hypothesized to occur in humans and these algorithms are adjusted to hormonal responses to sensory feedback from the environment. Anglophone countries have been severely disorganised by runaway capitalist development which has broken relationships with the land which have traditionally been used to navigate incest avoidance and the Westermarck effect, leading to a “chaotic soup.” Disrupted societies, be they of men or mice, have a tendency for unstoppable population growth and the overshoot of ecological resources.

Many collapseologist theorists have agreed with writers such as Jared Diamond in Collapse in seeing Easter Island (Rapanui) as a paradigm case of a society overshooting its ecological limits. However, Newman in the final chapter of her book sets out to show that this story is incorrect. In a fascinating critique she points out that there is no evidence that the Easter Islanders ever achieved population levels of 10,000 or even 5,000, and that demographic decline is poorly documented. Further, these people lasted 900 years before the collapse, which suspiciously enough occurred just before the arrival of Europeans. She notes that European trade wars over South American and other colonies had been occurring for more than a century, so it is implausible to suppose that Easter Island was in splendid isolation up to 1722. It is a more parsimonious explanation to posit that European contact led to Easter Island’s destruction, and there are in fact documents indicating that Europeans enslaved the people of Easter Island (see Benny Peiser, Energy and Environment, vol. 16, 2005, pp. 513-539). The population of Easter Island may never have exceeded 2,000 – 3,000 people.

In conclusion, Rules of Animal and Human Populations is a contribution to sociology of Weberian dimensions, combining innovative hypotheses, critical thinking of the highest calibre and a firm commitment to seek facts rather than be bound by politically correct dogmas. It is scholarship at its best which is now being frequently done outside the intellectually stifling confines of the modern university.

Review by Dr Peter Pirie, Professor Retired at University of Hawaii at Manoa:

This is an original, enjoyable and thought-provoking book which additionally, has the admirable virtue of quoting one of my works at some length. The paper cited was "Untangling the Myths and Realities of Fertility and Mortality in the Pacific Islands",(1997). "The Rules of Animal and Human Populations" examines the rules, workings and effects of economic, political and social systems as they have developed in modern societies as compared with the same systems as they applied to traditional societies. The Pacific Islands, because of their small dimensions, relatively recent human settlement and varied histories of colonialism are particularly useful as examples of the transitions. Newman's interest in my work lay in the instances I described in which Pacific Island populations did not conform to the theory of demographic transition.

For instance I suggested that the surge in fertility that followed the introduction of effective public health in most colonial territories was not, as was then commonly described, a return to "traditional" levels that had been disturbed by the introduction of alien diseases following their "discovery" and colonization by European powers. It was instead a destabilization that could lead to unsustainable population densities and poverty if not checked by limiting birth numbers or permitted emigration. In the absence of the vast majority of communicable diseases that could have depressed population densities, traditional societies on the Pacific islands employed an ingenious variety of ways of limiting human reproduction in the interests of keeping population densities in comfortable relationship with local resources. Among these stratagems were gender separation, customs which delayed marriage such as bride-price, prolonged lactation, post-partum taboos and temporary separations, attempted contraception, abortion and infanticide, deprecation of sexual interest, acceptance of homosexuality, and the encouragement of celibacy. All of these have been observed in recent times in isolated or less impacted populations such as remote atolls and in parts of New Guinea but also recorded in descendant cultures where contact has been more prolonged so that these practices may have been abandoned (or suppressed).

What I did not include in my primarily demographic account, because the anthropologists on whose work I depended never mentioned them, were incest avoidance" and the Westermarck Effect. The examination of these two is a major contribution of Newman's book. The way in which incest avoidance and and the Westermarck effect limit mating in proximate populations and therefore on the distribution and density of populations is particularly important in the Pacific Islands which characteristically are of small area and were populated recently compared to other regions and originally by small bands surmounting marine distances. In the future, demographers, sociologists, population geographers and particularly, anthropologists, will be unable to ignore these two forces, and need to be grateful to Sheila Newman for bringing them to our attention.

S. M Newman, Demography, Territory and Law: Rules of Animal and Human Populations, Countershock Press, Lulu.com, 2013 (paperback). Kindle and paperback version available from www.amazon.com. Order by mail from PO Box 1173, Frankston, VIC, Australia, 3199 or write to astridnova[AT]gmail.com. Or buy direct from Amazon.com or from Lulu.

Amid Australia's growing conflict over population numbers and democratic planning, we need ideas based on historical and social research, rather than shallow logistics pushed by technocrats. Familiar with these dynamics, I see the challenge of joining this debate with the depth it needs.

Amid Australia's growing conflict over population numbers and democratic planning, we need ideas based on historical and social research, rather than shallow logistics pushed by technocrats. Familiar with these dynamics, I see the challenge of joining this debate with the depth it needs.

Elephant seals have extraordinary sexual dimorphism where sexual competition has led to massive size and aggressive fighting between the males. Whilst the fighting between alpha elephant seals does not cause significant declines in their overall populations or life-support system, imagine if they had access to global finance and nuclear weapons.

Elephant seals have extraordinary sexual dimorphism where sexual competition has led to massive size and aggressive fighting between the males. Whilst the fighting between alpha elephant seals does not cause significant declines in their overall populations or life-support system, imagine if they had access to global finance and nuclear weapons. Age Discrimination Commissioner, Susan Ryan thinks that Treasurer Joe Hockey somehow deserves congratulations for suggesting that people's life expectancy may extend to 150 on the basis of some very speculative 'medical science'. [1] Futhermore, she's using this medical theory to jump on the moving retirement goal bandwagon. [2]

Age Discrimination Commissioner, Susan Ryan thinks that Treasurer Joe Hockey somehow deserves congratulations for suggesting that people's life expectancy may extend to 150 on the basis of some very speculative 'medical science'. [1] Futhermore, she's using this medical theory to jump on the moving retirement goal bandwagon. [2]

Reviews by Dr Joseph Wayne Smith and Professor Peter Pirie: "A contribution to [evolutionary] sociology of Weberian dimensions, combining innovative hypotheses, critical thinking of the highest calibre and a firm commitment to seek facts rather than be bound by politically correct dogmas. It is scholarship at its best ..." (Smith). "A major contribution of Newman's book is the examination of incest avoidance and the Westermarck Effect. The way in which incest avoidance and and the Westermarck effect limit mating in proximate populations and therefore on the distribution and density of populations is particularly important in the Pacific Islands which characteristically are of small area and were populated recently compared to other regions and originally by small bands surmounting marine distances. In the future, demographers, sociologists, population geographers and particularly, anthropologists, will be unable to ignore these two forces, and need to be grateful to Sheila Newman for bringing them to our attention." (Pirie)

Reviews by Dr Joseph Wayne Smith and Professor Peter Pirie: "A contribution to [evolutionary] sociology of Weberian dimensions, combining innovative hypotheses, critical thinking of the highest calibre and a firm commitment to seek facts rather than be bound by politically correct dogmas. It is scholarship at its best ..." (Smith). "A major contribution of Newman's book is the examination of incest avoidance and the Westermarck Effect. The way in which incest avoidance and and the Westermarck effect limit mating in proximate populations and therefore on the distribution and density of populations is particularly important in the Pacific Islands which characteristically are of small area and were populated recently compared to other regions and originally by small bands surmounting marine distances. In the future, demographers, sociologists, population geographers and particularly, anthropologists, will be unable to ignore these two forces, and need to be grateful to Sheila Newman for bringing them to our attention." (Pirie)

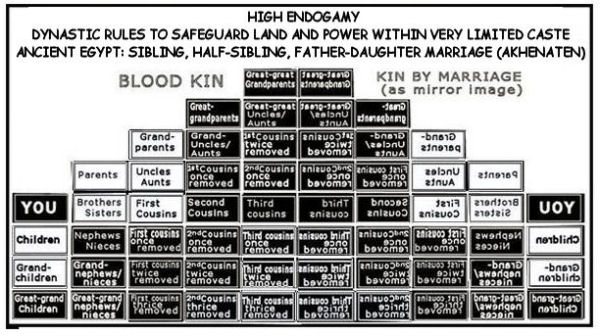

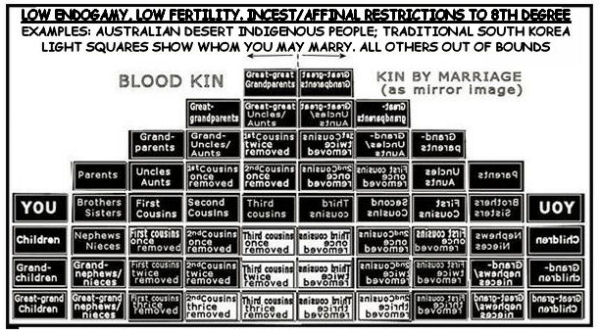

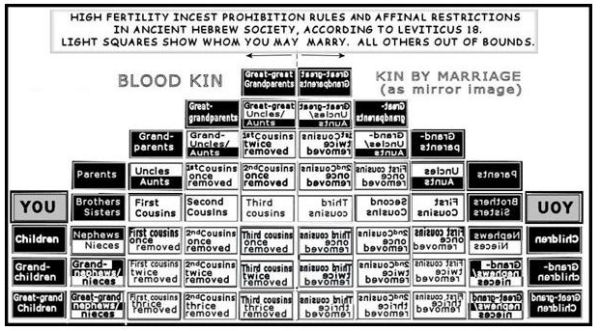

Outside the property development and population growth lobby, very few people who are worried about population growth and high immigration appreciate the effect of endogamy (marrying within your people) and exogamy (marrying outside your people) on population size and fertility. They also don’t recognize its effect on the private amassing of wealthy estates and political power. Anyone who wants to understand modern day problems with overpopulation, poverty, and loss of democracy would do well to study this article. This article is intended to stimulate debate about democracy, wealth distribution, and overpopulation. The author invites critical comments and argument.

Outside the property development and population growth lobby, very few people who are worried about population growth and high immigration appreciate the effect of endogamy (marrying within your people) and exogamy (marrying outside your people) on population size and fertility. They also don’t recognize its effect on the private amassing of wealthy estates and political power. Anyone who wants to understand modern day problems with overpopulation, poverty, and loss of democracy would do well to study this article. This article is intended to stimulate debate about democracy, wealth distribution, and overpopulation. The author invites critical comments and argument.

If you look at the white squares, you will see that the pharaohs of Ancient Egypt could marry their children and their grandchildren and other close relatives. The rigidity of this practice varied from pharaoh to pharaoh, and lesser relatives might also be married, however marriage within close blood relatives was encouraged.

If you look at the white squares, you will see that the pharaohs of Ancient Egypt could marry their children and their grandchildren and other close relatives. The rigidity of this practice varied from pharaoh to pharaoh, and lesser relatives might also be married, however marriage within close blood relatives was encouraged.

Recent comments