by Helga Vierich

Abstract:

Fire has long played a part in the ecology of the Kalahari Desert of Southern Africa. Among the Kua of the south-central Lalahari the power of natural and man-made fires is well understood. These hunter-gatherers use fire to control ticks, increase plant fruit yields, alter the species composition of wild plant communities, influence the movement of game, and to attract specific animals into snares and traps.

Introduction

I first met Hank Lewis at the American Anthropological Association Meetings in San Francisco. It was during the mid-seventies -1975, I think- and my first reaction was amazement: “I thought you were dead!” I had confused him with Omar Steward (who was dead). Both Steward and Lewis had assumed legendary stature in my mind at that time, since I had been reading everything I could get my hands on about the human use of fire as a tool for shaping the ecosystems. The Proceedings of the Tall Timbers Journal were like sacred works to me. Both Steward and Lewis were among those who had published on early human use of fire as a tool for environmental management. Lewis had reported ethnographic work among Cree and other groups of native hunter-gatherers in Northern Alberta. Steward had documented much the same in a more general way for all of North America. Their work was a revelation to me. Fire - something mentioned in the usual scenarios of human cultural evolution only in relation to cooking and comfort - was revealed as a tool of immense scope and power for managing entire ecosystems - a tool, moreover, easily accessible to hunter-gatherers long before actual domestication of plants and animals was even thought of.

Hank Lewis forgave me my gaffe. We found some coffee and a quiet corner; and settled into one of those long breathless talks that you can only have with someone who shares a mutual obsession. Hank had also written another paper of particular interest to me, on the possible role of controlled burning in the origins of farming in the Middle East. We talked for hours. I was enraptured by the idea of duplicating his observations on the use of fire among other hunter-gatherers. I also thought that the transition to agriculture could be better understood as a move from merely burning to burning and then planting. Hank Lewis was one of those at the very cutting edge; in fact, it seemed to me he had been one of those who had cut the edge. When I told him about wanting to follow, as it were, in his footsteps, he didn’t waste time being flattered. He told me two very important things that day: first, to collect as much information as possible about how the knowledge of burning was transmitted; secondly, to try to get concrete data on what effects fire actually produced in terms of plant productivity.

Less than eighteen months later, I found myself in the Kalahari.

I was extremely lucky in receiving twin blessings in the form of a wonderful thesis supervisor in the person of Richard Lee, and in that I had been funded by the National Research Council of Canada to study fire ecology among hunter-gatherers in Botswana. Then my luck ran out. In the weeks prior to my arrival, the Botswana government had been winding up a lengthy campaign to stop bushfires. Why? Well, Botswana had recently gained markets in Europe for its beef. Now cattle posts were rapidly expanding into the Kalahari as new boreholes made water available in the amounts required by cattle.

Fodder in the dry season was a major limitation, as hay was not generally cut and stored. Thus the dry wild grasses had come to be seen as a vital resource and the widespread practice of burning the dry veld was being widely condemned. Even in small villages, extension agents from the Ministry of Agriculture had announced that burning was now illegal. Fines and even prison sentences were to be given to anyone found guilty of setting fires in the bush. I had not known of this campaign before I arrived, since my correspondence had all been with the Ministry of Local Government and Lands, under whose authority fell all matters touching on the San -or BaSarwa - as the hunter-gatherers are called within Botswana.

For the next two years, no one would talk to me freely about the usefulness of fires set deliberately in the Kalahari - not the local farmers and cattle owners, most of whom were either Batswana or BaKalahadi; and certainly not the San, who in many cases worked for them as field hands or livestock herders. Among the San who were living in areas remote even from the cattle posts, people were still cautious. It was only after months of work on other topics that I was to gather information on indigenous knowledge of fire ecology.

This paper, for the first time, reports the results of these efforts. It is fitting that I write this in honour of Hank Lewis.

Helga Vierich

The People and their Setting

During the next three years, I surveyed the San who lived throughout the Kweneng district in the south eastern part of the Kalahari desert. Most of my more intense fieldwork was carried out among a group of people who call themselves the Kua. The region they inhabit includes part of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve and part of the northern Kweneng District of Botswana (Map 1). In the late 1970s they numbered some fifteen hundred, most of whom were still living entirely or seasonally by means of hunting and gathering.

There were varying degrees of employment in the farming and herding economy of their neighbours, the BaKalahadi and the BaKwena. Most of this work was for payment in-kind, in the form of cereal food, milk, and/or meat. Employment tended to take the form of traditional contractual arrangments, and was mutually opportunistic. It was clear from the employment histories and life histories collected that long-term relations between employers and employees were rare, in spite of the fact that the relations between San and these other ethnic groups had been previously described in the literature - and indeed by the employers themselves- as a sort of serfdom. It was also clear that the Kua, despite living for some centuries on the very edge of the ethnic boundary, had remained very flexible. In a lifetime, people might move back and forth between various economic options many times. Sometimes they spent a few years working as herders at cattleposts, and then returned to the life of independent hunter-gatherers. Often the change was occasioned by marriage or by changes in residential arrangments, rather than by any concerns of job availability or peaks in local supplies of wild animals or plants.

More water, more cattle, more ecological change

Many new boreholes have been drilled for water in this part of the Kalahari since 1950. With the securing of new and reliable water supplies came the cattle. Overgrazing has caused ecological change.

Since the push for more boreholes into the remoter part of the Kalahari, there has been an ongoing replacement of open grassland with thornbush within a five to ten kilometer radius of the waterpoints. The wild edible plants and animals preferred by the Kua already showed rapid decline in these areas by 1976. It was in such locations that the Kua found their options beginning to narrow. Even the cattle were regularly trekked out beyond the thornbelt to graze. At Dinonyane, one of the older boreholes, cattle were brought back to the borehole only every second day. Dew on vegetation was their only water for 48 hours.

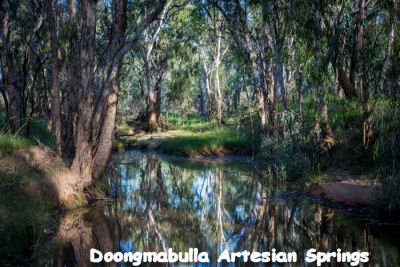

Sand creates natural water lenses

The Kalahari has been shaped by a pronounced shift between a wet and a dry season, imposed on a stratum of red sand. Dunes and broad, desiccated river valleys dominate a landscape dotted with salt pans. In rainy season these pans fill with water often only a foot deep, teeming with tiny shrimp. Some big pans, like the great Makadikadi pans of north-central Botswana covering hundred of square miles, fill with nesting flamingos and pelicans. Most of these pans are dry within weeks when the rains stop, and there are no streams or rivers flowing all year round[1]. But the sand has a secret. It is very deep - hundreds of meters in many areas - and rainwater seeps down into the sand until air pressure from air trapped in sand below overcomes the flow of water downward between the grains. This process forms water “lenses” which support a rich diversity of plant life. Rather than a sandy wasteland, the Kalahari is a kind of visually stunning open parkland, with beautiful groves of trees set at intervals over a rippling carpet of grasses and shrubs.

A rich ecosystem

This is an immensely rich ecosystem. It is full of tasty and nutritious fruits, nuts, vegetables, and tubers. It is home to over a dozen species of antelope, two species of rhinocerous, six species of cats (from lions to the ancestor of our own housecat), two species of hyena, several species of monkeys, three species of canids, a host of rodents and lagomorphs, as well as elephants, common zebra and cape buffalo; and about a billion birds, large and small and everything in between -including a few found nowhere else in the world. In the region occupied by the Kua, buffalo, elephants, and rhino had disappeared in living memory but had never been common.

Zebra were rare. The children were no longer aware of the word for some of these animals, but the adults told me that their word for the zebra was quag-ha - essentially the same as the word in the extinct language of the Cape Bushmen for their extinct form of zebra, a word we know in English as quagga. Many of the larger herbivores are migratory, as are many species of birds. The herds and flocks flow into the Kalahari during the rains, deeper and deeper as the landscape greens and becomes dotted with temporary waterpoints.

They flow out again as the seasonal drought advances, retreating to the more permanent rivers that flow on the edges of the Kalahari. A few antelopes remain year-round, like the gemsbok, the hardy little duiker, and the sable and khudu.

In the dry season the land is still fruitful, however, if one knows where to look. Many plants have stored up water and starches in their roots, bulbs, corms, or tubers. Even at the height of the dry season, a few hours walking and digging could yield 10-25 kg of such food, much of it surprisingly nutritious as well as flavorful.

Wild berries and tree fruits which survive the attentions of birds and eager human hands tend to dry up on the stem and take on the flavor and consistency of currents, edible well into the dry times.

As well, many plants produced seeds packaged with a dense energy supply to sustain germinatio - in other words, nuts. The Kua, like humans everywhere, know exactly what to do with nuts; and they live surrounded by some of the best nuts that have so far escaped the notice of the rest of the world. Chief among these are those produced by two closely related plants, the one a shrub, the other a vine, about which more will be said when we move on to consider the influence of fire.

The Kua camp in small groups comprising one to five families. I say camp to impress upon the reader the fluid and temporary nature of their traditional residential arrangements. The huts are small and made of local materials (branches and grasses). The people can move camp in a day, as the huts are easily built in a few hours. These arrangements suit the mobile way of life of the hunter-gatherer. When people are working for months or, occasionally, years on end for some family of BaKalahadi or BaKwena, they may stay put for the duration. In such cases they tend to make their camps larger and their huts bigger and more sturdy. Of such camps they say that they are building, not “BaSarwa” but rather “BaKalahadi” style homes. There was clearly a kind of ethnic identity emerging out of their dealings with other groups, for the Kua were quite explicit about what constituted a BaSarwa cultural trait or artifact as opposed to the things and customs and languages of their Bantu-speaking neighbours. Note that they spoke not of things Kua but rather of things BaSarwa, a kind of identification with other Koisan speaking peoples. This conception is remarkable in that in some cases they could not even speak to these other San, as in the case of their immediate neighbours to the south, who spoke a completely different Koisan language, !Xo. So when the Kua did start to speak of BaSarwa uses of fire, I paid attention.

Kua Uses of Fire: Informants’ Testimony

The Kua are adept at life in a harsh Eden. It soon became clear that they also were well aware of the potential benefits of controlled burning to keep it productive of the plants and animals they found most desirable. This use of fire appears to a form a traditional knowledge that children of both sexes are shown and taught by both parents. Knowledge of the use and effects of fires in the environment was part of general knowledge; and even though the sexes tended to use fire differently, girls did not acquire separate kinds of knowledge from boys. There was considerable flexibility about both genders learning all the important subsistence tasks. For instance, there was one young woman who ran an active trap line, as she had been shown by her father and brothers. She also used the knowledge of how fires affected animal behaviour, which she had learned from both parents. Most girls did not do this. They were not interested.*

The information and observations recorded below were collected in the final eight months of fieldwork among the Kua, and cannot possibly exhaust the scope of their knowledge or extent of their practices. They fall into two rough categories: men’s fires and women’s fires. Men’s fires generally were intended to attract game and lure animals to specific traps, snares, or ambushes.

Women’s fires were generally set to keep plant communities stable (inducing a fire climax?), to increase the yield of specific plants (especially nuts), and to thin out the undergrowth in areas frequently walked - so that thorns were not constantly getting caught in toes, and snakes and scorpions were easily spotted - and to control biting insects like fleas and ticks. The bigger the fire’s spread, the more people were involved in monitoring it. So sometimes almost everyone in the camp group would be involved in monitoring a fire, no matter whether it was a man’s fire or a woman’s.

Monitoring a fire usually involved keeping the fire within bounds, especially if the wind turned the fire toward another settlement or towards one’s own camp. Fires were very carefully monitored if set in the dry season (rare) and less so if set in the early part of the rainy season (most common). All of these activities took place against a background of natural fires caused by lightning, which became more frequent in a pattern that followed behind the frequency of human-set fires; in other words, more and more often as the first big thunderstorms heralded the beginning of the rains. The most dangerous natural fires are those that started during a “dry” thunderstorm in early spring (September/October). Even these were not the disasters seen in heavily forested areas in other parts of the world, since most fires in the Kalahari travel along the ground by jumping through little clumps of grass. It is easy to simply step or hop over the fire. The wild animals and the livestock know this and simply move quietly ahead, around or through the path of a fire.

Visions of large game being stampeded into hunters’ traps did not survive my first Kalahari fire. The Kua howled with laughter over the very idea.

Instead, they showed me how it was really done, if one wanted to use fire to hunt. These were generally men’s fires. If a person found a small area that had burned naturally or created one, then snares could be set along game trails leading to this area. Animals, it was explained, liked to come to a recent burn. They came to lick ash (most antelope, especially duikers), to have their young (sable antelope), and to eat the new growth of grass and other plants that tended to follow within a week of the fire (all herbivores). Of course, if snares were set they had to be closely monitored since all the predators also knew about the attraction of herbivores to recent burns. Next, if one found a tree that had had the misfortune to be struck by lightning, or if one found a dead tree and set fire to it oneself, one could set snares all around the tree. The man who told me this was then persuaded by his wife to take me out to his latest set of snares set around such a tree. If a camp was abandoned after someone died there -people were buried in the sand under their hut- the huts were usually burned. This practice was known to attract ostriches which liked to bathe in the dense ash piles where the huts had stood. Snares could be set to catch the birds by their feet; or better yet, by their necks, since an ostrich can often batter a snare to pieces with its powerful legs. To catch an ostrich by the neck one put a charred white piece of bone in the circle of the snare (photo). Ostriches in the Kalahari are always on the lookout for hard chunks of material like this because they need it to help grind up the food in their gizzards. There are few rocks to be had, save the hard white kernels of calcrite that work their way to the surface at pans. In the area where I was shown the bone snare, the nearest such pan was ten kilometers away. Aside from the fact that the snare did in fact have a strangled ostrich in it the next day, I must admit reflecting on the way that ostriches are often presented in cartoons - as creatures with a strange habit of swallowing all manner of unlikely materials like tin can and shoes. Is it all to do with an unhappy gizzard?

Women going out to gather often took along some hot coals wrapped in damp leaves if they anticipated having to light a fire to cook lunch on the road, so to speak. This only happened when the foods they were after were located more than a few hours from camp. In the way it was explained to me, it was most often on these occasions, at the end of the dry season, that they might set fires to specific areas to encourage higher yields, the germination of particular food plants, or the discouragment of undesirable plants*. The particular plants at the heart of these activities were two species bearing nutlike beans, Bauhinia esculenta Burch. and Bauhinia macrantha Oliv.. B. esculenta grows as a vine; and has an underground storage organ that is also a prized food item when found on a young plant.**

B. macrantha is a low shrub which has no tuber. Both species produce large leathery pod contianing up to ten hardshelled nuts.

These are flattened ovals; dark brown in colour when roasted, and are extremely high in protein and fat. These plants are critically important food sources during the dry season. Fire, I was told, could improve the yield of both plants. It also improved the visibility of the seed pods in the case of the vine. Recalling Hank Lewis’ suggestions, I resolved to investigate further.

Effects of Fire on B. esculenta: Field Observations

In the course of my travels along the bush tracks, I frequently came across areas which had burned on one side of the track and not on the other. Frequently, this afforded an excellent opportunity to measure the effects of the fire on an identical plant community, with the burned and “control” areas seperated by the track. There were also areas where the fire had died after burning a small area along and even across the road, leaving part of the same plant community untouched. I took the opportunity afforded by these examples of “burned” and “control” zones to record the immediate and subsequent effects of the fire on the plants.

I decided to limit my observations to areas in which fire had occured in and near Bauhinia macrantha stands. Three meter square parcels were marked off a random number of paces from the road*.

This procedure was done in pairs, one on the burned and one on the unburned area. I counted the number of plants but also the number of white blossoms and seed pods on each plant. The results were tabulated in terms of the number of blossoms and pods per plant, not per plot.

The results showed a striking difference between the fruitfulness of plants burned and unburned. The plants in burned parcels showed a 2 to 23% increase in pods and flowers. The average was close to 12% if the lowest and highest scoring plots were ignored (Table 1).

Unfortunately my sample size was small (only five areas and only twenty sets of plot counts) but time was short as I was coming to the end of my fieldwork. I also began to doubt that the results would be typical because of the lack of rain that year. The burning tended to coincide with the end of the dry season and the beginning of the rainy season. That year (1979/80) the rains failed. It was one of the lowest rainfall years since records began to be kept in Botswana (Diagram 1). Also, my time was limited as I had been hired by the Botswana Ministry of Agriculture to undertake a survey of the effects of the drought on the welfare of people in the Kalahari. This task was especially urgent because the Kweneng District, where I was doing my fieldwork, was one of the areas hardest hit.

Conclusion

I offer these results, however, for what they are worth. I know Hank Lewis was intrigued because we talked about my findings when I first came to teach at the University of Alberta in 1989/90. He also felt, as I did, that both the numbers and the circumstances of my study limited the usefulness of my findings. Nonetheless, having seen much of the literature on hunter-gatherer use of fire for environmental manipulation, I must admit that I do not think these observations quite deserved to languish in the obscurity to which my earlier, more critical self had consigned them. I only wish this work could have been a more worthy salute to the man whose influence inspired me to do it in the first place. In fact, I wish that Hank was still here.

----------------------------------------------------------------

NOTES

[1] Except for the Okavango, a vast inland delta far to the north. In some areas the Kua told of places where there had been year-round springs attracting large herds as the dry season set in, but all of these had been occupied for generations by “people of the cattle.” The seasonal hunting bonanza such locations would have afforded to hunter-gatherers were long past..

*[2] I asked them. They mostly rolled their eyes and giggled in disbelief: “me? hunt? it’s too hard - let the boys do it.” (rough translation of the guist of their replies) In fact the teenaged girls seemed for the most part, quite uninterested in anything but their social lives. They hung out together and gossiped about boys, oiled each other’s skin and distained helping their mothers with the foodquest. They often had to be shamed into doing any work. Teenaged boys, like the girls, tended to be preoccupied with affairs of the heart, but they did seem to take a more enthusiastic view of learning hunting skills. This is not, I suspect, due to the inherently more exciting nature of hunting. Older men often told me that hunting was a boring, generally unrewarding task. You walk all over the place all day and were often hungry.

Only one hunt in four was successful and hunters were not accorded any special status. But the boys viewed learning to hunt as a welcome relief from babysitting in camp under the eye of their grandmothers while their mothers and teenage sisters were out gathering - or worse, being cajoled into coming along and helping gather wild plants.

*[3] which they called by the same word, meaning weeding, that the BaKalahadi used to describe the more usual practice of weeding their gardens ..

** [4] Older specimens can weigh over fifty kilograms but are too tough to eat, although they are sometimes used in tanning leather.

*[5] I put pieces of paper marked with number (multiples of five) into a hat and shook and withdraw at each location anew.

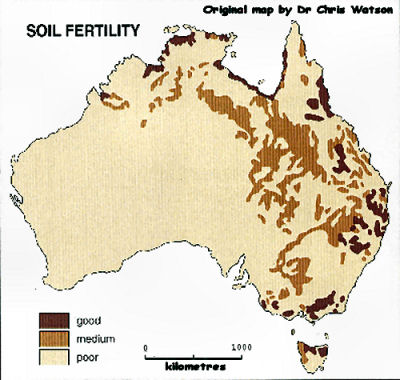

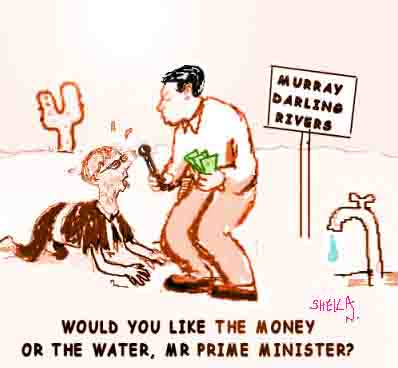

To keep up with global food demand, the UN estimates, six million ha of new farmland will be needed every year. Instead, 12 million ha are lost every year through soil degradation. Australia lost 36 million ha of agricultural land in just the four years from 2005 till 2009. Some of this lost land has occurred because of urban sprawl which is swallowing up some of our best soils close to cities that used to supply the fresh fruit and vegetables. A scathing report by the Royal Commission has gone as far to accuse the Murray-Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) of negligence and being "incapable of acting lawfully," apparently because they overestimated the amount of water returned to the river by a factor of ten. The many warning signs all around us are continually ignored by politicians obsessed with economic theories that defy even the basic laws of mathematics.

To keep up with global food demand, the UN estimates, six million ha of new farmland will be needed every year. Instead, 12 million ha are lost every year through soil degradation. Australia lost 36 million ha of agricultural land in just the four years from 2005 till 2009. Some of this lost land has occurred because of urban sprawl which is swallowing up some of our best soils close to cities that used to supply the fresh fruit and vegetables. A scathing report by the Royal Commission has gone as far to accuse the Murray-Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) of negligence and being "incapable of acting lawfully," apparently because they overestimated the amount of water returned to the river by a factor of ten. The many warning signs all around us are continually ignored by politicians obsessed with economic theories that defy even the basic laws of mathematics.

In the light of the upcoming

In the light of the upcoming

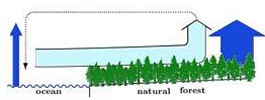

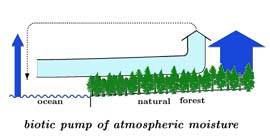

Whilst many people have been aware (but have mostly been ignored) that vegetation, especially forests, creates rain, and whilst desertification has been linked to deforestation historically many times, there is a new and robust theory to explain how this may happen.

Whilst many people have been aware (but have mostly been ignored) that vegetation, especially forests, creates rain, and whilst desertification has been linked to deforestation historically many times, there is a new and robust theory to explain how this may happen.

Recent comments