Murray has since become one of Britain’s most important human rights campaigners, a fierce advocate for Julian Assange and a supporter of Scottish independence. His coverage of the trial of former Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond, who was acquitted of sexual assault charges, saw him charged with contempt of court and sentenced to eight months in prison. The very dubious sentence, which upends most legal norms, was delivered, his supporters argue, to prevent him from testifying as a witness in the Spanish criminal case against UC Global Director David Morales. The company founder is being prosecuted for allegedly installing a surveillance system in the Ecuadorean Embassy when Julian Assange found refuge, that was used to record the privileged communications between Assange and his lawyers. Morales is alleged to have carried out this surveillance for the CIA.

CH: Craig Murray, the former British Ambassador to Uzbekistan was removed from his post after he made public the widespread use of torture by the Uzbek government and the CIA. He has since become one of Britain’s most important human rights campaigners, a fierce advocate for Julian Assange, and a supporter of Scottish independence. His coverage of the trial of former Scottish First Minister, Alex Salmond, who was acquitted of sexual assault charges, saw him charged with contempt of court and sentenced to eight months in prison. The very dubious sentence, which upends most legal norms, was delivered, his supporters argue, to prevent him from testifying as a witness in the Spanish criminal case against UC Global Director David Morales who is being prosecuted for allegedly installing a surveillance system in the Ecuadorian Embassy when Julian Assange found refuge there, that was used to record the privileged communications between Assange and his lawyers. Morales is alleged to have carried out this surveillance on behalf of the CIA. Joining me to discuss his case is Craig Murray. So Craig, before we talk about the rather complicated judicial procedures that have been leveled against you--charges that have been leveled against you, let’s talk about UC Global and Julian Assange. You, I think, did probably the best coverage of the trial and have written, you know, very presciently and eloquently about Julian’s case.

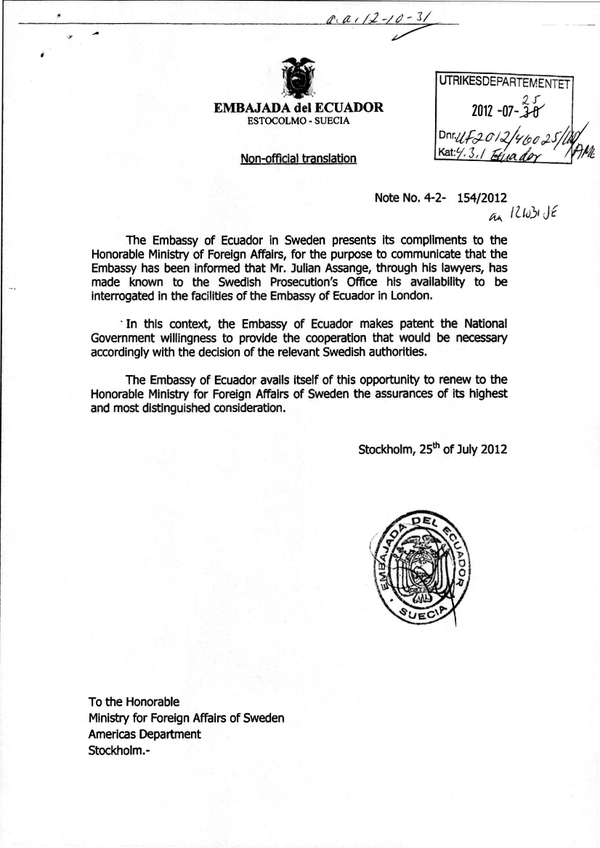

CM: Thank you. Yes. UC Global was spying, specifically, on Julian’s defense counsel, and on meetings Julian had in which he was discussing his defense, and the evidence is--and the evidence that’s been given in court is, by former employees of UC Global who have turned whistleblower, that that was at the behest of the CIA. And of course, this is quite extraordinary. The idea that the government which was trying to extradite Julian Assange, was spying on his legally privileged conversations with his counsel to defend that extradition. In any normal course, anywhere, in any Western so-called democracy, that would be enough to have the case dismissed in itself. That hasn’t been the view taken by the London courts. The counsel for the US government claimed that due to Chinese walls, the CIA have never given the Justice Department any of the material which the CIA had obtained on the defense counsel. In which case, why were the CIA specifically instructing UC Global to spy on the defense counsel if they weren’t going to use the material? What other use could the CIA be putting that material to, you know? It’s plainly nonsense. You don’t--you don’t tell a company to spy specifically on somebody’s lawyers if you’re not going to use it in the legal case. So this whole thing is a [INDISTINCT] of lies and evasion, and it all goes back to the--to the CIA and the state department.

CH: So we should be clear that a lot of the stuff is leaked, El Pais, and other newspapers. So we have videos that they took inside. You know, the leaks, this isn’t conjecture. Can you--a lot of this evidence has become public. Can you lay out, you know, what we’ve been able to see, especially in the Spanish press?

CM: Yeah, certainly. The Spanish press has, you know, put out in some detail that the employees have testified that they were ordered specifically to spy on the defense counsel. The video material itself has been leaked to the media. You can find it online, including video material of my own conversations with Julian, because it wasn’t only his legal counsel who were spied upon. And as well as that, you know, it’s been leaked that there were discussions of potentially poisoning and killing Julian Assange. There were discussions on kidnapping him, there were discussions on obtaining material like nappies of his babies, so their DNA could be mapped and the parenthood checked. The--and also, not discussions, what actually happened was not just videoing his lawyers, but following his lawyers away from the embassy, tracking them to their homes, surveilling them more generally. And in fact, there have been burglaries at offices of some of his lawyers, which, so far, evidence hasn’t directly linked to UC Global, but we--it seems almost certainly was.

CH: And for those of us who visited, I visited Julian a couple of times, we had to turn over all of our electronics to the UC Global security system, and we now know, from these leaks, that our information was copied, is that true?

CM: That’s absolutely right. In fact, you know, both you and I are, I think, in a situation where, you know, all the information, as well telephones has been--has been taken and given to the CIA by UC Global.

CH: So let’s talk a little bit about--and this isn’t the first time you’ve run into a confrontation with the CIA as ambassador to Uzbekistan. You exposed the widespread use of torture on detainees held at the behest of the CIA by the Uzbek government. And so you, you know, for many years, have I think been a--safe to say, a target. I know we can talk about what’s happening at this moment, but before we got to this moment, where you’ve been charged with contempt of court and we can talk about, you know, how they’ve kind of twisted legal normalities to get to that verdict, what--since you left the diplomatic service, and then especially during your long campaign, you’re quite close to Julian, have you seen other attempts to essentially criminalize you in any way?

CM: Well, very much so. And it should be said, of course, that the CIA was actively shipping people to Uzbekistan from other countries, in order for them to be tortured, that they were sending people there to be tortured, taking them on the CIA-controlled rendition flights, and one of the things that happened was Tashkent being a small place, I used to actually meet and talk with the people who physically did the renditions with the pilots who flew them in. So, you know, there’s no doubt at all that was happening, and I was able to provide with my testimony as to it happening. At that time, I was threatened repeatedly with prosecution under the Official Secrets Act which carries very long jail terms, and in many ways, it’s the equivalent of the Espionage Act which Julian is now--is now charged. Those didn’t--that didn’t happen in the end, and these that didn’t happen. It was under the Official Secrets Act. In those days, you got a jury trial, and the jury would have had to decide whether to send me to jail or not. And we have hesitance and particularly the late and great whistleblower Clive Ponting who blew the whistle on British publications that deliberately inflamed and led to full warfare in the Malvinas, or Falkland Islands, with the sinking of General Belgrano. He leaked information that the Belgrano was in fact steaming away from the islands at the time we sank it, killing many hundreds of people. He undoubtedly leaked that information and should have been jailed under the Official Secrets Act legally, strictly, but the jury refused to convict him because the jury felt he had done the right thing. And in my case, the government felt that they tried to convict me under the Official Secrets Act. It was extremely likely the jury would refuse to convict even though I was, you know, openly admitting to having leaked the material and to doing my best to whistle-blow on them and stop CIA torture. So that was a difficult period, when I was expecting potentially to be jailed for a long time. I’ve face numerous legal threats, and so like many whistleblowers, I’ve had evidence, and first-hand evidence of government interference every time I tried to get a job [INDISTINCT] with the government going and talking to potential employers and telling them not to employ me. I’ve had a great deal of surveillance and intimidatory surveillance, and those kinds of things. So it’s a climate, that in many ways, I got used to it, and which, to be honest, serious national security whistleblowers have to get used to it, it’s what is going to happen to you if you become a national security whistleblower.

CH: You have stood up for other people who are being persecuted. I mean, you’ve really become quite an important voice within the UK. And you sat in on this trial with Salmond. And just--we have a minute and a half before we have a break, but just lay out what he was being charged with, which you found to be--or you always believe was untrue.

CM: Basically, there were accusations from nine women of sexual assaults, which went at one end of the spectrum from the actual attempted rape, possible attempted rape, to the other end of the spectrum, putting a knee on somebody--a hand on somebody’s knee in a--in a car. But the circumstances of each of the accusations was staged in ways I can’t really detail here. And the--and the women all knew each other, and were all very closely connected to each other, and were--and the majority of them were extremely close allies of the current First Minister of Scotland. And they’re stories were--just didn’t work, they just didn’t match, and ultimately, he was acquitted by the jury. So that’s what made me suspicious of the entire thing when I first heard of it. There were aspects to their stories which just didn’t square with known facts, and that led me to start my investigation.

CH: Great. When we come back, we’ll continue our conversation with Craig Murray. Welcome back to On Contact. We continue our conversation with Craig Murray about his trial, conviction, and appeal. So you sat in on a courtroom. It was a very brief trial, wasn’t it? And I read through twice the--what they’ve charged you with. It’s really quite obscure and not very clear. They essentially blame you for identifying those witnesses but you never named them. Just, you know, explain, you know, how they’ve essentially twisted the legal framework to go after you.

CM: Yeah. No, this is--this is quite extraordinary. I’ve been found in contempt by Jigsaw Identification. And that means not that I named anyone and not that I personally identified anyone but that I gave clues in what I vote, which put together with other information that could be found elsewhere in the public domain might enable or make it lightly in legal terms that somebody could identify someone. There was no evidence at all presented to court anybody had been identified as a result of anything I published. But the idea was that somebody could be identified. And if I can give one example, if a piece of information I’d written in reporting the defense case were added together with another piece of information which six years previously and unbeknown to me had been published on page six of the regional newspaper. And that were added together to a piece of information in a book which I had never read and heard anyone else had ever read either. If you put those three together, that would give you sufficient clues to work out who somebody was, what was--was the argument. Some of them were more direct than that, I mean, some of them saying if you put together what I said with the BBC report, then those two might give you enough clues to work out who somebody was. It’s an extraordinary thing because, of course, it makes it almost impossible for any reporter to know what somebody else knows or know what the BBC are going to report or to say anything at all about the events that happened and who was involved, without the chance that you’re giving a little bit of extra information that may enable somebody to reveal an identity. And it’s extremely--it’s called Jigsaw Identification. That’s what courts formally call it. It’s not called batting statutes. This is a construct the courts have been--have come up with in their history of finding ways to enforce contempt laws. And of course it’s not total--it’s not totally daft. The idea is is that if somebody is a protected witness, you shouldn’t be able to say that they live in such and such streets. They work in such and such profession. They drive a red car. They were born in this town. And then say, “Oh, I didn’t publish for them therefore I’m not guilty.” I mean, you can understand why there is a law that prevents you getting at an identity by publishing clues. It’s not unreasonable to have such a law. It’s just that in this case, they’ve used it at an extreme stretch to say that little bits of information I gave out and gave out solely in the context of reporting the case of the defense could, added together with other things from a wide variety of places, help be a clue that help find an identity.

CH: This sentence of, you know, this prison sentence, what’s the legal basis for it? It, you know, of course there’s no legal basis now to hold Julian in Belmarsh. One hopes this isn’t endemic throughout the UK judicial system but how do they justify the sense? And I think one of the things that struck me when I read through this is that they also said that it didn’t matter what intent was, that even if you had no intent to expose the identities of these women, you still would be found guilty.

CM: Yeah, it’s what they call in the UK and possibly they use the same terminology in the US. It’s what they call an offense of strict liability, that if you do it, even if you do it by accident, you are just as guilty. And possession of narcotics is perhaps an example of the best known offense of strict liability, saying I didn’t know I had them isn’t an excuse. You have them, you have them and you’re going to jail. That was quite extraordinary because, I mean, one thing I will say, I want to make absolutely plain, I have no intent whatsoever to reveal these identities and I do not believe I did reveal them. And I most certainly did not intend to reveal them. The judgment does says there’s no--there’s no requirement for intent in the legislation. Intent doesn’t have to be--has to be pilgrim. They did gratuitously asked--they did gratuitously add that they believed I did have intent despite there having been no evidence whatsoever given of intent. And the hearing only lasted an hour and a half. And it had no evidence for anybody had identified anybody. And no evidence of intent but then the verdict said that I had been deliberately trying to put out names or deliberately trying to identify people. And the prison sentence was because this would cause, you know, potentially serious harm to protect the witnesses or prevent other protected witnesses from coming forward based on no evidential basis whatsoever. Very, very peculiar judgment. And I should say my defense team can’t find any evidence of anyone publishing, anyone from the media, old media or new media, having been jailed for contempt for over 40 years in the UK. People just don’t get jailed for contempt of court. And there are rulings of the European Court of Human Rights to which, you know, just gotten the subject which state unequivocally that normally you shouldn’t be jailing journalists. If a journalist does do something wrong, they or their media organization should be fined. And, but it--you know, to actually jail journalists for writing things is a very serious intrusion upon freedom of speech.

CH: Okay. Let’s just from the broad picture why are they doing this and what do they hope to accomplish?

CM: I think it’s several things coming together. And, of course, there was no jury in my trial. And I sent you the note , when I became a whistleblower, they were very keen to put me in prison but that--they couldn’t find a way of doing it without the obstacle of a jury. I think they finally--the state--the establishment has finally found a way to imprison me without a jury. There’s also the fact that what this is about is that there’s a split in the independence group. And the reason, they were trying to frame Alex Salmond and I should be totally blamed. I have no doubt whatsoever that this was an attempt to fit up Alex Salmond on false charges orchestrated by those currently in charge of his--in party, particularly orchestrated by the current First Minister of Scotland. And that this attempt to frame him was foiled by the jury. The jury saw through it. And the reason for this, the split in the Scottish National Movement was behind this is that Alex Salmond and I and others believe that the movement has been hijacked by people who have no intention of actually obtaining Scottish independence. And what this is about is putting a lid on people like me who support Scottish independence actively and really want Scottish independence shortly. And I should say there are four or five other--the speech prosecutions. Prosecutions for what I would call court crime currently active in Scotland. I’m not the--I’m not the only one. And all of them against independence supporters. In fact, there are five prosecutions and four of them are of people I know, which shows you that it’s a close group being picked upon all for just saying things. So I think the motives are essentially critical.

CH: I think also--I mean, wouldn’t you agree you’ve already become a lightning rod because you are one of the most prominent and vocal defenders of Julian Assange;.

CM: Well, I think that certainly lays behind a lot of it. I mean, my relationship to Julian and my relation to WikiLeaks and my having a platform which is widely read internationally which could expose the shenanigans of the--of the court hearings against Julian. I think that certainly increased the market labor costs, willingness--the state’s willingness to try to shut me up and imprison me, yes. There’s no doubt that’s in play here.

CH: And just to close last 50 seconds, you are--you and your lawyers are appealing this decision, is that where we are?

CM: Yes, we filed our appeal to the Supreme Court today. I have a stay of imprisonment until the 6th of July in order to enable me to appeal to the Supreme Court and that’s what we’re now--we’re now doing.

CH: And if the Supreme Court decides not to hear your appeal, what happens?

CM: At that stage, I’ll go to prison. Though strongly, I will be appealing to the European Court of Human Rights.

CH: Great. Thank you very much. That was Craig Murray on his trial, conviction, and his struggle for appeal over his coverage of the trial of former Scottish Minister Alex Salmond.

From this coming Thursday 11 July, weekly protests outside the office of Mark Dreyfus will resume, in support of David McBride, Daniel Duggan (pictured left) and Richard Boyle, at 1pm outside the electoral office of Federal Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus (pictured right). Mark Dreyfus' electorate office for the seat of Isaacs, is located at 566 Main Street Mordialloc, Victoria, 3195.

From this coming Thursday 11 July, weekly protests outside the office of Mark Dreyfus will resume, in support of David McBride, Daniel Duggan (pictured left) and Richard Boyle, at 1pm outside the electoral office of Federal Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus (pictured right). Mark Dreyfus' electorate office for the seat of Isaacs, is located at 566 Main Street Mordialloc, Victoria, 3195.

The UK parliament is currently evaluating changes to the UK Official Secrets Act that would see jail for life for people who let others know of law-breaking in government and corporations (whistleblowers). Changes to the Act are aimed to prevent any public interest journalism. Journalist Mohamed Elmaazi reports on the draft legislation in fascinating and chilling detail in John Kiriakos' interview. Public interest would be erased as a defense.

The UK parliament is currently evaluating changes to the UK Official Secrets Act that would see jail for life for people who let others know of law-breaking in government and corporations (whistleblowers). Changes to the Act are aimed to prevent any public interest journalism. Journalist Mohamed Elmaazi reports on the draft legislation in fascinating and chilling detail in John Kiriakos' interview. Public interest would be erased as a defense. In person and

In person and

Every Friday at Sydney Town Hall, this group continues to stand up for Julian Assange. Stirring speeches about Australia's whistleblowers and Australia's involvement in war-crimes, Albanese's failure towards Assange, our crocodile tears for the prisoners of other regimes, but not for Julian Assange.

Every Friday at Sydney Town Hall, this group continues to stand up for Julian Assange. Stirring speeches about Australia's whistleblowers and Australia's involvement in war-crimes, Albanese's failure towards Assange, our crocodile tears for the prisoners of other regimes, but not for Julian Assange. In this extraordinary interview, revealing more political abuse of the British legal system, Chris Hedges talks to Craig Murray, the former British ambassador to Uzbekistan, who was removed from his post after he made public the widespread use of torture by the Uzbek government and the CIA.

In this extraordinary interview, revealing more political abuse of the British legal system, Chris Hedges talks to Craig Murray, the former British ambassador to Uzbekistan, who was removed from his post after he made public the widespread use of torture by the Uzbek government and the CIA.

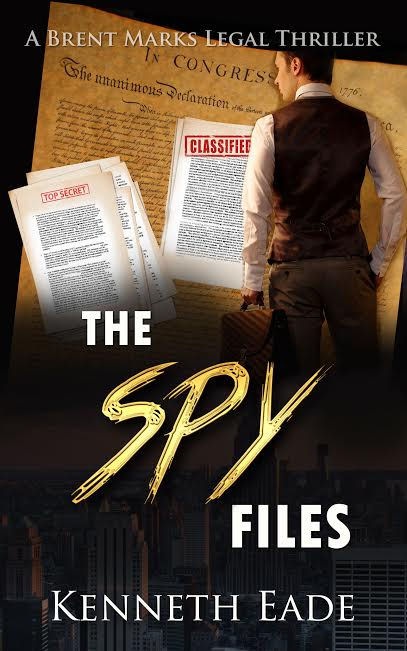

Kenneth Eade is a legal thriller writer who chooses difficult and original subjects, of the kind that preoccupy candobetter.net readers and authors. This article foreruns the imminent publication of The Spy Files and is based on Kenneth's research for that novel. See also

Kenneth Eade is a legal thriller writer who chooses difficult and original subjects, of the kind that preoccupy candobetter.net readers and authors. This article foreruns the imminent publication of The Spy Files and is based on Kenneth's research for that novel. See also

Recent comments