21.5% of Melbourne's sewage is currently recycled to Class A or C recycled water standard. This is mainly used on market gardens, open spaces, golf courses, vineyards and to reduce dust at construction sites. Most of the remaining treated effluent is discharged into Port Phillip Bay and Bass Straits under accredited EPA licences.

21.5% of Melbourne's sewage is currently recycled to Class A or C recycled water standard. This is mainly used on market gardens, open spaces, golf courses, vineyards and to reduce dust at construction sites. Most of the remaining treated effluent is discharged into Port Phillip Bay and Bass Straits under accredited EPA licences.

Clean Ocean Victoria spends a lot of time protesting about the pollution in the bay which is associated with these discharges, and advocating that these 'outfalls' be recycled. For no good reason, the government has been ignoring these recommendations by Clean Ocean for years. Now there is a plan to trash the network of pipes that supplies recycled water to Melbourne's market gardens, just to build more suburbs to satisfy the construction lobby's demand for more immigrants to buy houses. In the mean-time we are subjected to constant harassment from the Victorian government to make us use less water. We also watch helplessly as tyrants facilitate a ridiculously expensive desalination plant - in electrical, financial and environmental terms - and deliver us up to it as customers.

Putting the cart before the horse

We have here an example both of the damage done in the service of unnecessary population growth and the failure to offset some of that damage by retaining a superb working food production area which also puts water to excellent re-use. Yet we are still subjected to harangues by suprisingly well-publicised so-called 'green' activists who basically argue for 'smart growth' and have been doing so for years in the face of the entrenchment of just the opposite. You can't help wondering what's in it for them.

For instance, in his article, ,"A growing population is not the problem" Cam Walker, (Friends of the Earth) tries to argue that population growth isn't important because we should really be reducing our ecological impact. He has been saying this for years in the face of exponential increases in consumption in our throwaway society. Now he is saying it in the face of massive acceleration of population growth.

In fact, Cam just sounds like another member of the growth lobby. If he isn't getting paid by them, he certainly should be.

Cam, by the way, is also incorrect in asserting that all recycled Melbourne water is dumped into the bay. Currently the Eastern Treatment plant in Carrum supplies the Eastern Irrigation Scheme in Cranbourne.

see:

http://www.ourwater.vic.gov.au/programs/recycling/eastern-treatment-plant and http://www.topaq.com.au/project.htm

State government to trash agriculturally important water recycling system in greater Melbourne

This is a network of pipes that supplies recycled water to market gardens.(Simple explanation of where Melbourne's sewer water goes that includes the market gardens.)

This area has just been designated part of the Cranbourne growth corridor (but has not yet passed into law by the Victorian upper house) which means that the agricultural market garden area and the associated pipeline infrastructure from the Carrum Eastern Treatment Plant (sewage treatment plant), will be under houses in the next few years.

I only learned of this in a presentation recently by a planning official from the City of Casey (which covers the Cranbourne area). City of Casey has proposed that the agricultural areas will be protected and they are prepared to sacrifice other rural areas in the city (City of Casey is on the urban fringe) so as to save the market gardens. But the state government didn't listen to them. City of Casey sees the market gardens as a significant employer and part of the Bunyip-watershed food-bowl region.

Those of us who worry about rising prices for vegetables in shops can also see how important these metropolitan cheaply watered sources of food are.

Market gardens sacrificed for more housing for more people

They have also had an area that was designated as industrial rezoned to housing by the state government. This was an area that the City of Casey had hoped would serve as a centre of employment for its residents. The state government has changed this. This means that the new (and existing) residents of Casey will have less opportunity to live and work in the same area, directly contradicting any desire for sustainability that has been expressed in other government policies.

Displaced Victorian farmers unable to find new well-watered land to restart market gardens

One of the people at the forum commented that the market gardeners who are prepared to sell and move further out (into Gippsland) have been unable to buy land that is still close to the urban fringe that has the same access to water supply as the one in Cranbourne.

The planning official said that the Victorian government's view is that there is no consequence in forcing out market gardeners from Melbourne because it places a much higher priority on adding to our population rather than planning for our future.

Comments by editor

Once most of us were self-sufficient and working for wages was done to supplement our incomes. Big business didn't like this because it meant that people had a choice about whether they would work for wages or simply please themselves. The main way that big business, working hand in hand with government, removed our choice in this matter was to remove our rights to land and soil. This was done in England famously through laws favoring big land-owners taking land from small land-owners and taking public land and enclosing it, supposedly for more efficient production. In colonies like Australia, everyone started out with food gardens. Even places like hospitals and schools had food gardens. But, using the same process, corrupt governments worked with big business and big agriculture to get control of food production, and the food transport. For those of us who do have enough land for a vegetable garden in the suburbs, local governments work to remove our rights to use our gardens to their fullest extent, with rules about what animals we can keep and what we can do in built-up areas. We are expected to move on if our suburb becomes built up; we are losing the rights we had to protect what we had. Now we work so hard anyway, that few of us have the time to build up a viable garden - even though growing food does not require much labour overall. It is only if you want to grow food for profit that you need to work very hard to produce a lot more than you need for yourself.

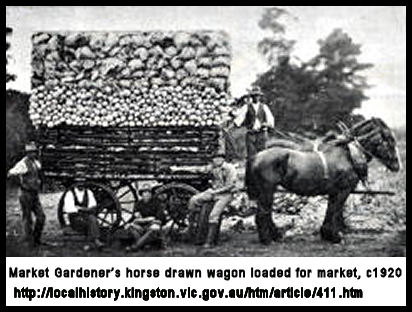

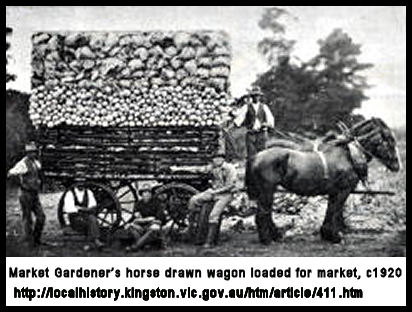

"Along with domestic food production in backyards, market gardens traditionally supplied most of Melbourne's vegetable requirements. Early gardens were located along Merri Creek and the Yarra and Maribyrnong rivers, and from the 1840s English, Scots and Irish families established gardens in the sandbelt localities of Brighton, Moorabbin, Bentleigh and Cheltenham. Following the gold rush, many Chinese immigrants moved to the metropolis and established market gardens, mostly along watercourses in northern and eastern suburbs including Heidelberg and Coburg. These gardens made a vital contribution to the metropolitan vegetable supply until the early decades of the 20th century, when increasing taxes and rates, combined with rising land values, made subdivision a more lucrative proposition for the landowners. The 1920s saw the commencement of Italian market gardening in Werribee (still an important area for vegetable production), and the introduction of motorised trucks. These joined the traditional cavalcades of carts piled high with vegetables which would converge on city markets and return to the gardens laden with manure from urban stables. In the 1880s some growers also fertilised their crops with nightsoil purchased from contractors. World War II necessitated a large expansion in vegetable production. While semi-rural districts such as Glen Waverley were noted in the prewar decades for their well-ordered countryside of orchards and market gardens, by the late 1950s the once substantial acreages of growers like Jim Stocks, the Cauliflower King of Ashwood, were being subsumed by suburban expansion. Where once vegetables grew within a few hundred metres of Camberwell Town Hall, postwar developments in transport and post-harvest technologies have seen even outer suburban market gardens increasingly replaced by large-scale capital-intensive vegetable farms located further from the metropolis.

Andrea Gaynor

References

Monk, Joanne, 'The diggers in the trenches: a history of market gardens in Victoria 1835-1939', Australian Garden History, vol. 4, no. 1, July/August 1992, pp. 3-5. Details Source

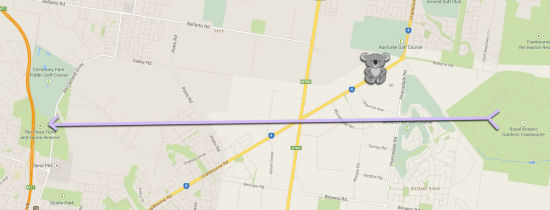

Today at the Australian Wildlife Protection Council AGM I interviewed Craig Thomson, Animalia wildlife carer, about the events that may have led to Sean the Koala travelling down a busy highway in Langwarrin. Turns out he was probably following a traditional migratory route of male koalas in search of romance, which takes them from islands of habitat like the Cranbourne Botanical Gardens, down four-lane highways towards The Pines Flora and Fauna Reserve in Frankston, or further south, across the massive Peninsula Link tollway that cuts the Peninsula in half. Why are koalas being forced onto highways? It is another terrible cost of the unwanted human population expansion that is being forced on Victorians by the State Government, in its bid to grow Melbourne faster and faster. Animalia has $10,000 outstanding power bills; you can help by donating to WESTPAC BANK BSB 033138 Account 434072

Today at the Australian Wildlife Protection Council AGM I interviewed Craig Thomson, Animalia wildlife carer, about the events that may have led to Sean the Koala travelling down a busy highway in Langwarrin. Turns out he was probably following a traditional migratory route of male koalas in search of romance, which takes them from islands of habitat like the Cranbourne Botanical Gardens, down four-lane highways towards The Pines Flora and Fauna Reserve in Frankston, or further south, across the massive Peninsula Link tollway that cuts the Peninsula in half. Why are koalas being forced onto highways? It is another terrible cost of the unwanted human population expansion that is being forced on Victorians by the State Government, in its bid to grow Melbourne faster and faster. Animalia has $10,000 outstanding power bills; you can help by donating to WESTPAC BANK BSB 033138 Account 434072

Recent comments