You might have heard of "Volunteering Australia" recently—perhaps your volunteer coordinator offered you cheap sugary cookies to celebrate "National Volunteering Australia Day," leaving you puzzled about how these ended up in your local animal welfare fridge. Shades of Victoria Nuland in Ukraine, you may have thought, suspiciously. What’s behind this hype? How did Volunteering Australia Day seemingly rise to prominence, becoming something akin to a politically correct alternative to Australia Day? Is there money in it?

You might have heard of "Volunteering Australia" recently—perhaps your volunteer coordinator offered you cheap sugary cookies to celebrate "National Volunteering Australia Day," leaving you puzzled about how these ended up in your local animal welfare fridge. Shades of Victoria Nuland in Ukraine, you may have thought, suspiciously. What’s behind this hype? How did Volunteering Australia Day seemingly rise to prominence, becoming something akin to a politically correct alternative to Australia Day? Is there money in it?

Why is Volunteering Australia pushing volunteers to submit personal details and adhere to 'Codes of Conduct' and 'Working with Children' permits just to weed local reserves or join the new state-local bodies — that explicitly state they will not be selected on consideration of past contributions and they will have no influence on policy?

Is there a link to the cancellation of longstanding volunteer organizations in favor of council-State-designated groups, as seen with the recent changes to environmental groups in Frankston ahead of the new Activity Centre? Is this another way of excluding any but the most obedient, unquestioning people from coordinated activity?

When did volunteering shift from grassroots, free association among community members, to a government-controlled initiative, micromanaged by bureaucrats and specific insurance  companies? Doesn’t this new approach undermine self-determination, creating a second-class of citizens who need official permission to engage in collective action or activities?

companies? Doesn’t this new approach undermine self-determination, creating a second-class of citizens who need official permission to engage in collective action or activities?

Is it true that Volunteering Australia is part of a broad UN campaign to popularise and integrate volunteering into development, involving governments, NGOs, and communities? What does this mean? We look into this and other things below.

Codes of Conduct for Volunteers?

Since no consideration passes between volunteers and the organisations they work with, (volunteers by definition, work without payment or expectation of reward), one would not expect that the codes they are increasingly required to sign would constitute legal contracts. And they are not a legal requirement, as Volunteering Australia admits. Volunteering Australia has positioned itself not just as a standard-bearer but as the default authority on volunteer selection criteria. With the implicit authority of an unstated relationship[1] with the Federal Government, it lays down the law:

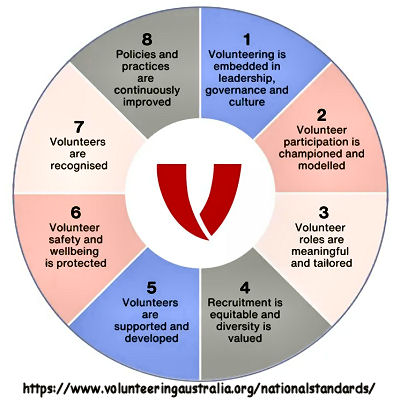

The National Standards for Volunteer Involvement (National Standards) are a best practice framework to guide volunteer involvement. They are an essential resource for all organisations and groups that engage volunteers. The National Standards can be used flexibly, recognising that volunteering takes place in highly diverse settings and ways.

Adoption of the National Standards has direct benefits to both volunteers and to organisations and groups:

- They help improve the volunteer experience and ensure that the wellbeing of volunteers is supported and their contributions are valued.

- They provide best practice guidance and benchmarks to help organisations attract, manage and retain volunteers and support effective risk and safety practices. [...]

Insurance and commissions

And it sounds like a good source of business for AON, Volunteering Australia's official insurer. "Aon has been a proud supporting partner of Volunteering Australia for over 20 years. By working closely together, and leveraging our longstanding relationship with insurers, we’ve developed an understanding of the risks not-for-profits face and helped design cover that caters to these risks." Volunteering Australia states that "Volunteering Australia receives a commission from Aon in relation to its endorsement as our supporting partner and approved insurance provider. (See https://www.volunteeringaustralia.org/57630-zkkvkm/#/)

There is money in volunteering, but not for volunteers, of course.

Volunteering Australia estimates that there is $290 billion worth of volunteer labor in Australia:

"Volunteering is a tower of strength in our communities with 5.8 million Australians or 31 per cent of the population volunteering, making an estimated annual contribution of $290 billion to our economic and social good." (https://www.volunteeringaustralia.org/57630-zkkvkm/#/)

Volunteer labor is estimated to be worth around $33 per hour on average. Whilst people do work for nothing in areas that are meaningful for them, when they can afford to, there are numerous volunteers who work for welfare benefits in various charities, where management and CEOs receive compensation. This situation can be seen as a form of coerced unpaid labor, often influenced by socioeconomic factors. It goes against the traditional definition of volunteering, which emphasizes the absence of coercion. When volunteering is tied to survival needs, it raises questions about the true voluntariness of such contributions.

It's noteworthy that while Australian salaries remain low and work conditions continue to decline, a significant portion of the workforce is made up of people working for free or receiving the dole, which is well below a livable wage.

How did it all become so formal, with big-salaried CEOs, and international UN connections?

The shift from pre-1997’s lean budgets and lower salaries to today’s structured funding and codification reflects a broader trend of NFP professionalization, potentially distancing sincere, spontaneous grassroots efforts.

What does Volunteering Australia do with your Personal Information?

Regarding ethical use of information, Volunteering Australia’s practices appear compliant, with transparent policies and data breach protocols (e.g., Privacy Amendment Act 2017). However, the practice of sharing volunteer data with third parties (e.g., councils, Not For Profits) and retaining it indefinitely raises concerns about overreach, especially for sensitive council/state and personal data. The current CEO, Mark Pearce, has a commercial background in, among others, Goldman Sachs and Mandala Advisory in Melbourne/Sydney. Mandala’s consulting for Not For Profits involved economic modeling that could leverage volunteer data. A data-driven approach could potentially prioritize efficiency over privacy. No breaches are reported, but the commercial lens and United Nations Sustainable Development Goals ties (e.g., International Volunteer Years 2026 - IVY 2026) need scrutiny for centralized data use.

What is the risk in United Nations Sustainable Development Goals links?

The UN is made up of many bodies and programs and it is the only global forum that records and publishes political debates from every country, as in, for example, the UN Security Council TV at https://webtv.un.org/en/search/categories/meetings-events/security-council, which we have often linked to. Getting rid of the UN would be a mistake. There are programs, however, which can be used to carry out soft 'regime-changes,' and the Sustainable Development Goals may well be one of those.

The IVY 2026, co-sponsored by 54 countries, including Armenia, Bolivia, Fiji, Germany, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kiribati, and Turkmenistan, was proclaimed by the UN General Assembly via UN Resolution A/RES/78/127 (December 2023), in December 2023. It is a global initiative led by United Nations Volunteers (UNV) to promote volunteerism as a driver for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It is a broad UN campaign to popularise and integrate volunteering into development, involving governments, NGOs, and communities. Why might this hold risks of centralised data collection, and what does that mean?

According to Poe.com AI:

Connections with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can imply centralized data usage and associated risks in several ways:

Measurement and Reporting: Organizations aligned with the SDGs often need to collect and analyze data to demonstrate their impact. This can lead to centralized databases where sensitive information is stored for tracking progress.

Accountability Demands: The SDGs emphasize accountability and transparency. However, this can pressure organizations to aggregate data in a centralized system to provide comprehensive reports, potentially increasing the risk of data breaches.

Standardization of Data: To align with global goals, organizations may standardize data collection methods, leading to centralized repositories that aggregate information from various sources, heightening privacy concerns.

Resource Allocation: Centralized data systems may be used to optimize resource allocation based on perceived needs related to the SDGs. This could lead to prioritizing efficiency over individual privacy rights.

Potential for Misuse: The focus on achieving specific outcomes linked to the SDGs might encourage organizations to leverage centralized data in ways that risk exploiting personal information for strategic advantages.

The SDGs promote societal change, so we need to carefully consider how data is managed and the associated risks of centralization. We also need to be aware that Australia has subscribed to this program, and its values. Some SDG projects are controversial, although we are rarely aware of their links to Australian events and programs. Some of these controversial goals have benign names like 'Urban Development,' 'Water Management,' and 'Refugee Support.'

Urban Development (SDG 11): The Plan for Victoria (2025) pushes 1.78 million homes by 2051, driving high-rises in about 60 suburbs to date, from Frankston to Camberwell, and beyond, without proper community input. The relevant amendments to planning have been called out in parliament as an abuse of democracy and are widely labeled a 'authoritarian planning.' These depend on substituting State for Local government in the Activity Centre areas, and create a potential no-man's land where no-one has clear residential rights, and Body Corporates reign. Commercial housing-supply programs, including Rent-to-Buy are encouraged, often through behemoth transnationals like Vanguard and BlackRock. Such commercial privately controlled programs are motivated to supply less and less land to more and more people because supplying land is not seen as a public cost, but a commercial profit opportunity. Likewise, commercialising land-supply often supports very expensive and environmentally disruptive projects like Metropolitan Activity Centres.

Water Management (SDG 6): Water is increasingly privatised in Australia under the rationale of efficiency, with efficiency judged on economic rather than ecological, human rights, and human survival criteria. The Murray-Darling Basin Plan’s water trading raises rural costs ($100/ML in 2024), prioritizing commercial profit over locally self-determined and managed agriculture. These commercial water-management programs are motivated to supply less and less water to more and more people because supplying water is not seen as a public cost, but a commercial profit. Likewise, commercialising water supply often supports very expensive and environmentally disruptive projects like desalination plants, which have been guaranteed profits by governments, such as the Steve Bracks Victorian government.

Refugee Support (SDG 10): Volunteer programs (e.g., Red Cross) aid migrant integration, linked to high immigration policies. Of course refugees need help, but Australia uses the concept of refugees to market high migration from non-refugee sources. The idea is to make people who want to help refugees believe that all migrants are refugees and so a big immigration program is taken to mean helping lots of refugees. On the other side, for people who see refugees as maybe dangerous terrorists or some such, mass immigration will seem threatening, but objections will seem mean or ill-judged. The real problem of creating refugees is not addressed, i.e. support for wars that destroy economies and landscapes, creating humanitarian and economic refugees. Australia only takes about 14,000 refugees per annum, but imports more than half a million non-refugee immigrants. Australia's immigration programs also chronically poach educated migrants from countries recovering from wars and upset economies.

Australian Volunteer Coordination pre-1997 comparison:

Before Volunteering Australia’s formation in 1997, volunteering coordinators (e.g., small Not For Profits with AUD 50,000–100,000 budgets) handled data manually, often without formal privacy policies, relying on trust in community groups (e.g., Lions Clubs). Budgets were lean (AUD 100,000–200,000 in 2025 dollars), and salaries were low (AUD 60,000–100,000 today for coordinators). No centralized data sharing existed, reducing privacy risks but lacking Volunteering Australia’s current safeguards. In contrast, Volunteering Australia has some very high-powered staff,[3] used to working in finance, banking, and big-profile charities.

NOTES

[2] Associate Professor Mark Lyons, Centre for Australian Community Organisations and Management, Faculty of Business, University of Technology, Sydney, "Australia's Nonprofit Sector," S5.1 Australia's nonprofit organisations, by Field of Activity - 1995-96, https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/featurearticlesbytitle/309CE684C5DA1915CA2570FF007F8C9B?OpenDocument

Add comment