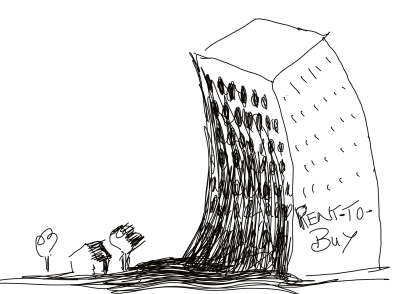

In housing markets today, the rise of rent-to-buy schemes purports to offer new opportunities for potential homeowners. These schemes portray an apparently promising pathway for the many individuals who cannot qualify for traditional mortgages in Australia's outrageously overpriced market, allowing them to rent a property with the option to purchase it later. Whilst buyers should always be wary of schemes that seem to make the unaffordable affordable, the increasing involvement of large transnational companies like Vanguard and BlackRock in these schemes further complicates the landscape, raising critical questions about fairness, tenant rights, and market dynamics.

In housing markets today, the rise of rent-to-buy schemes purports to offer new opportunities for potential homeowners. These schemes portray an apparently promising pathway for the many individuals who cannot qualify for traditional mortgages in Australia's outrageously overpriced market, allowing them to rent a property with the option to purchase it later. Whilst buyers should always be wary of schemes that seem to make the unaffordable affordable, the increasing involvement of large transnational companies like Vanguard and BlackRock in these schemes further complicates the landscape, raising critical questions about fairness, tenant rights, and market dynamics.

At the heart of rent to buy schemes is the promise of home ownership. They invite tenants to gradually work towards purchasing a property while living in it, often with a portion of  their rent contributing to the eventual purchase price. This model is obviously particularly appealing in a climate where housing prices are stratospheric. The shiny sales-pitches mask big pitfalls, of course. Many tenants find themselves ensnared in murkey agreements, leading to confusion over their rights and responsibilities. Reports of exploitation are common, with individuals facing high fees, unclear terms, and a lack of real legal protections that leave them vulnerable.

their rent contributing to the eventual purchase price. This model is obviously particularly appealing in a climate where housing prices are stratospheric. The shiny sales-pitches mask big pitfalls, of course. Many tenants find themselves ensnared in murkey agreements, leading to confusion over their rights and responsibilities. Reports of exploitation are common, with individuals facing high fees, unclear terms, and a lack of real legal protections that leave them vulnerable.

The situation is further exacerbated by the growing competition for housing globally. As demand surges, large corporations are able to leverage their financial power to secure favorable terms and outbid individual buyers. This dominance creates a market environment that prioritizes corporate interests over those of tenants. These companies seek enormous profits and advocate for policies that benefit them, at the expense of tenant protections. Endebted governments, eager for any investment, provide tax incentives and ease regulations, fostering an environment ripe for exploitation.

The regulatory landscape surrounding rent to buy schemes varies significantly across countries. In some regions, relatively robust tenant protections exist, giving some measure of transparency and fairness. However, in many others, where regulations are lax, tenants find themselves ill-equipped to defend their rights. The imbalance of power between large corporations and individual renters makes it difficult or impossible to challenge unfair practices, leaving many feeling trapped in unfair contracts.

Tenants' rights gained in less chiselling times have eroded. Schemes like rent to buy from monster-corporations usher a return to 19th century misery, under governments that care much more about corporate kickbacks than the basic welfare of constituents. Even that is an understatement, since in Australia, governments are increasingly undistinguishable from transnational corporations themselves. We live here in a time where even the option of taking shelter in a tent means paying high rents in caravan parks, or risking big fines, or even prison, for camping in bushland, reserves and on roadsides. Without shelter, human existence becomes impossible, and the current situation highlights the fundamental indecency of Australian government, both federal and state.

Add comment