Why did the David Hicks case attract so much public support in Australia, when Julian Assange’s apparently does not? The establishment press was still a lot freer in Australia then. It still covered anti-war protests, protest against the introduction of new terrorism laws, and even Hicks’s scandalous treatment by the Australian government. It’s not doing that for Assange.

Why did the David Hicks case attract so much public support in Australia, when Julian Assange’s apparently does not? The establishment press was still a lot freer in Australia then. It still covered anti-war protests, protest against the introduction of new terrorism laws, and even Hicks’s scandalous treatment by the Australian government. It’s not doing that for Assange.

Why did the David Hicks case attract so much public support in Australia, when Julian Assange’s apparently does not? Perhaps mainstream coverage of the Abu Ghraib scandal (uncovered by Wikileaks) helped raise Hicks's profile by making people realise how shocking the Bush Administration post-9-11 US military prison system was? Although deteriorating, the mainstream press was still a lot freer in Australia then. It still covered anti-war protests, protest against the introduction of new terrorism laws, and even Hicks’s scandalous treatment by the Australian government. It’s not doing that for Assange. Even the Australian Law Council tried to help Hicks. It sent out over twenty press releases, a public letter to parliament, and various reports, including three from its independent observer at Hicks’s trial, but it has little at all to say about Julian Assange.[1]

It seemed that the Australian public during Hicks’s imprisonment, especially in South Australia, Hicks’s home state, was more capable of organising on its own behalf, less directed by MSN propaganda, nor as divided and disorganised by mass migration, multiple suburban infills, exhausting commuting, and personal and familial isolation.

In fact, Hicks and Assange had a number of commonalities before they ever hit the news. They were both free-range children of the 1970s. From fractured families, with fractured educations, they emerged as highly original and energetic idealists, each seeking to be a freedom fighter in his own way. And both ran up against the ultimate warlord, with the most prisoners in the world, the United States. Even more shockingly, their persecution was and is cynically aided and abetted by their own Australian government, highlighting the low regard in which it holds we citizens.

Although David Hicks was actually taken prisoner after he had purposefully (and not unlawfully) been involved with foreign militias in Pakistan and Afghanistan, his run-in with the United States was an accident of US foreign policy changes. Ironically, he went from a total unknown to purportedly ‘the most dangerous man in the world’ because he happened to be in Afghanistan when the United States declared war on Afghanistan’s government (the Taliban) subsequent to 9/11.

Julian Assange’s persecution was not a coincidence. He was not in the wrong place at the wrong time, but in a new place and time when technology and his skills put him in a position to reveal ‘the matrix’ to the world. Privy to the multiple state secrets deposited in the Wikileaks drop box, he knew the degree of state corruption and ruthlessness. In the face of this, his persistence was courageous. His assistance to Snowden and his own flight to the Ecuadorean Embassy demontrated clear awareness of how criminally vengeful the United States would be.

Nevertheless, when the United States came after him, portraying him similarly to Bin Laden, and his defenders scattered, Assange’s disillusion must have been all the worse. Until that time, Wikileaks had been supported, and Assange had personally been feted, as a freedom-fighting publisher and editor, by the mass media and high profile elites all over the world. It almost looked as if good was going to overcome evil.

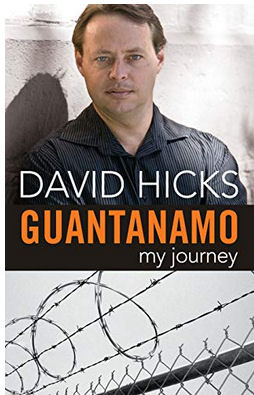

Perhaps, where Assange does not resemble David Hicks, is that he deeply threatens the United States, as the keeper of a vast store of its most awful secrets about the many crimes of its powerful. However, Hicks’s defenders and Hicks’s autobiography, (Guantanamo, my journey, Heinemann 2010) exposed a large swathe of US crimes in Guantanamo’s operation, the illegality of the military commission, the utter lawlessness, abject immorality and psychopathy of the way it treats its prisoners. So much so that Hicks’s book was and is virtually unobtainable and unknown in the United States.

A similarity for both men is that they are Australian citizens and that Australians should be tried under Australian law. The US extending its jurisdiction to foreign nationals while others cannot do the same is a huge problem. Assange is not a criminal and nor was David Hicks, but powerful criminals in charge of states, like despotic medieval princes, have been able to imprison them despite this. There have been numerous attempts to trap Assange and plans to assassinate him. Like David Hicks, he has been held in solitary confinement 23 hours a day, without any charge.

A surprising ray of light in all this darkness is that both men’s fathers, absent or distant in the early years, finally rose brilliantly to their sons’ defence.

David Hicks

David Hicks was born on 7 August 1975. Hicks grew up in South Australia, increasingly lonely within a series of family blends that resulted from his father’s three marriages. He went to several schools but left, with his father’s permission, at 15. He was intelligent, but bored or depressed, and seeking an identity and a group that he could relate to. He had the unusual idea, for a suburban South Australian boy, of training for work on cattle stations up north, where he learned to be a skilled horse-rider. This skill and his short, light build, led to employment pre-training racehorses in Japan. There, he met an Israeli street trader who inspired him with the idea of both of them travelling along the Asian silk road on horseback, but Hicks injured his ankle and had to go back to Australia instead. Returning to another racehorse job in Japan, in 2008, Hicks was so moved by mainstream media accounts of conflict and oppression in Kosovo, that he decided to go over and help the Muslims there. In Albania, he experienced for the first time the solidarity of people fighting for their lives. When the war ended, back in Australia, his lived experience and passion for international justice and travel set him apart.

David Hicks was born on 7 August 1975. Hicks grew up in South Australia, increasingly lonely within a series of family blends that resulted from his father’s three marriages. He went to several schools but left, with his father’s permission, at 15. He was intelligent, but bored or depressed, and seeking an identity and a group that he could relate to. He had the unusual idea, for a suburban South Australian boy, of training for work on cattle stations up north, where he learned to be a skilled horse-rider. This skill and his short, light build, led to employment pre-training racehorses in Japan. There, he met an Israeli street trader who inspired him with the idea of both of them travelling along the Asian silk road on horseback, but Hicks injured his ankle and had to go back to Australia instead. Returning to another racehorse job in Japan, in 2008, Hicks was so moved by mainstream media accounts of conflict and oppression in Kosovo, that he decided to go over and help the Muslims there. In Albania, he experienced for the first time the solidarity of people fighting for their lives. When the war ended, back in Australia, his lived experience and passion for international justice and travel set him apart.

He tried unsuccessfully to get involved in helping East Timor and also to join the Australian army. Although he was not religious and would bawk at proselytising, he joined a Muslim sect in a local mosque, hoping for discussion about justice and self-determination in faraway landscapes.

Australian legislation of the time only made engaging in conflict overseas illegal if it involved overthrowing a government. Supporting one or liberating a province was legal.

Hicks’s next involvement in local struggles over Kashmir between India and Pakistan, reads more like an idealistically-themed way of seeing the world and meeting people than a firm committment to a particular national ideology. It seems he was beginning to question it, anyhow, when 9-11 happened and the US got involved in Afghanistan, where Hicks happened then to be. On 9 December 2001, as he was attempting to get away from hostilities and make his way back to Australia, he was kidnapped and sold to US Special Forces.

Hicks finished up at Guantanamo Bay Prison, where he was kept for about five years in solitary confinement in tiny cells, with little protection from heat and cold, minimal food, and almost no exercise. Without Geneva conventions or habeas corpus, he was also repeatedly mentally and physically tortured, and denied information about any crime he was charged with nor how long he would be there.

After three years Hicks was charged with conspiracy, attempted murder and aiding the enemy, and committed to face trial, but on 29 June 2006, the US Supreme Court ruled in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld that the military commissions set up by George Bush to try people at Guantanamo Bay Prison were illegal under United States law and the Geneva Conventions. The commission that was to try Hicks was abolished and the charges against him voided leaving him in limbo. Instead of releasing Hicks, an Act of US Congress reestablished the military commission system and Hicks was charged again, this time for ‘providing material support for terrorism.’

The Australian government betrayed Hicks’ human right to justice by advising his lawyers to tell Hicks that he would only receive Australian Government support if he pleaded guilty to whatever he was accused of. This culminated in an “Alford plea,” which is a form of plea bargain where the defendent does not admit guilt, but still pleads ‘guilty.’ This was Hicks only hope of ever being released from Guantanamo Bay. On 26 March 2007, he was sentenced to seven years in addition to the five years he had already been detained, however the sentence was suspended except for nine months. Hicks himself had little or no idea of what was going on. He was coerced at every step.

On 20 May 2007, Hicks arrived at an Adelaide RAAF base, from which he was taken to Adelaide’s Yatala Labour Prison, where he was kept in solitary confinement in the highest security ward, until 29 December 2007, after which he was placed under a control order by the Australian Federal Police, until December 2008.

In July 2011, the Australian Government attempted to prevent Hicks from benefiting from proceeds of the sales of his autobiography by arguing that they were proceeds of crime, but they dropped these proceedings by July 2012, since his guilty plea would probably not have been admissable in court, due to its having been obtained by torture and other forms of duress.

In October 2012, the United States Court of Appeals held that Hicks’s conviction was invalid since the law he was convicted under had not existed at the time of his alleged crime and conviction canot be retrospective.

On 19 November 2012, on Q&A Hicks asked Prime Minister John Howard a question via video, as to whether he believed that Hicks was treated humanely and that the military commission was a fair system. John Howard said, among other things, words to the effect that Hicks was guilty because he had pleaded guilty. The Q&A compere Tony Jones then observed that it was widely known that John Howard’s office had advised Hicks’s lawyers that he needed to plead guilty in order to get out of that prison. Howard denied knowing anything about this, but his denial was hard to believe, especially from the way that Howard was still denouncing Hicks as a criminal. You can view these exchanges here : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QQO3pW0DLmI

Was David Hicks a criminal or a hero? Well, basically, he survived a prison that was declared illegal by the Supreme Court of the State it claimed to represent, after years of solitary confinement and horrible physical and mental torture. No crime on Hicks’s part was proven nor seems likely, but there were definitely terrible crimes committed by the US military against David Hicks and others in Guantanamo and similar extraterritorial US prisons all over the world.

Hicks lived to write a riveting autobiography that revealed intelligence, curiosity, empathy, originality and insight. It carefully described these crimes against him and against other victims detained there. His story has been generally corroborated by a number of other ex-prisoners of Guantanamo Prison, [see for instance https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=Guantanamo+Bay+survivors] so there is no doubt of the criminal conditions he was sold into by his Northern Alliance kidnappers. In my mind, and in the minds of many Australians, his denunciation of the criminal conduct and values of the US military commission system makes David Hicks a hero. British prisoners in Guantanamo were liberated by the British Government because it held that it could not leave citizens where they had no human rights. But the Australian Government left David Hicks in that situation for years.

What does that say about the Australian Government ? You might say, well, that was the John Howard Government, however Julian Assange has been treated in the same way by successive Australian Governments, including the Albanese Government. To me that says that the Australian Government has maintained a shameful and cowardly record of supporting criminal human rights abuses against its own citizens, when perpetrated by the United States government, and that it should be notorious for this.

Julian Assange

Julian Assange was born on 3 July 1971, four years before David Hicks. Assange’s biological father was John Shipton, an anti-war activist, but Assange was raised by his mother Christine Hawkins, and step-father, Richard Assange. They ran a small theatre company, travelling frequently, but divorced after 7 years. (Richard Assange died in 2012.) Moving house frequently, Assange attended many different schools, as well as being home-schooled or via correspondence. When he was about 20, he was charged with computer hacking, although given minimal punishment in view of his age and non-criminal intentions. He obviously developed values, associations, and friendships, with people such as human rights and whistleblower strategist, Susan Drefus, through this ubiquitous modern medium. Although Julian dropped out of university, he had become highly skilled at computer coding, had contacts and friends in this field. He designed Wikileaks in 2006, which ‘specializes in the analysis and publication of large datasets of censored or otherwise restricted official materials involving war, spying and corruption’ and electronically safeguards the anonymity of its sources.

NOTES

[1] From searches at the Law Council of Australian site for David Hicks and for Julian Assange :

https://

Add comment